UMPQUA, Ore. —

Fifty years is a long time. In some cases, a lifetime. For my Grandpa Scott, though, 1969 might as well be yesterday. He vividly remembers man’s first steps on the moon, in part, because he helped get American astronauts there.

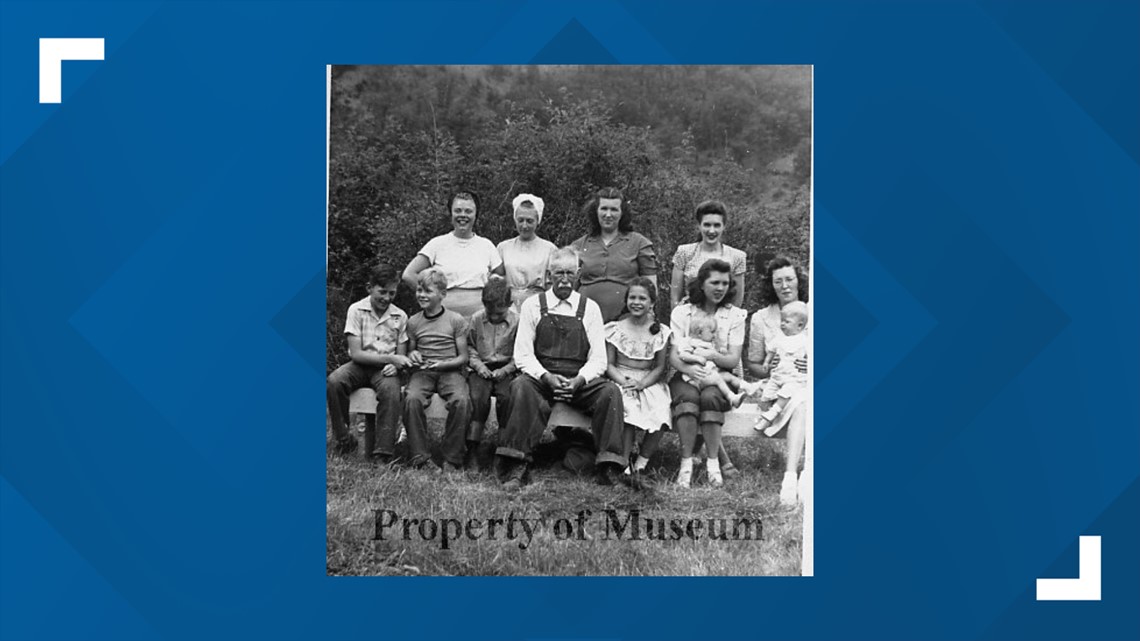

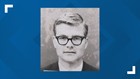

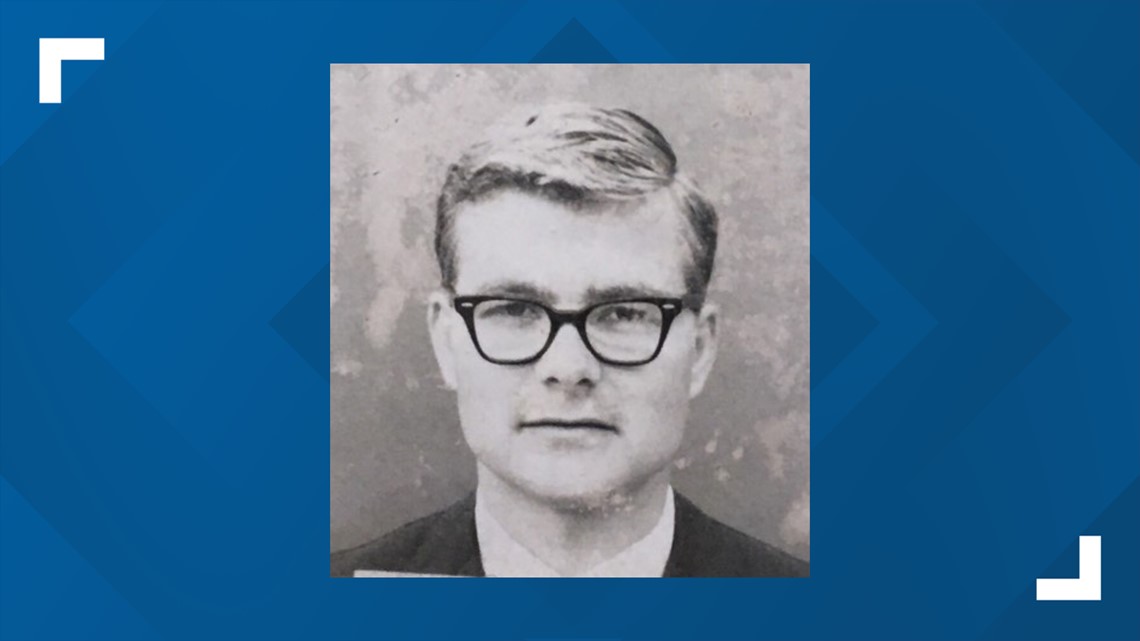

Let’s back up. The man I call “Grandpa Scott” and who my kids have dubbed “Great Scott” is legally Calvin Scott Henry III. My mother's father was raised in Umpqua, Ore., which has a booming population of 112, according to Wikipedia. When he was growing up, even fewer people lived there, but the community did have its own school. Umpqua School was a one-room schoolhouse that my grandpa attended through eighth grade, after which he attended and graduated from Roseburg High School.

“When I grew up, I thought I was going to be a farmer or rancher,” he told me.

That changed during freshman orientation at Oregon State College, what is now Oregon State University. Deans from the various schools were sharing with students the different areas of study available to them. The engineering school representative caught Henry’s attention.

“He said, ‘I want 20 people in the front row to stand up. Now 18 of you sit down. The two who are left will graduate from the School of Engineering,’” remembered Henry. “That was quite a challenge. I thought, ‘Well, my God, I'll give it a try.’”

You should know my grandpa doesn’t try. He just does. By 1959, he'd earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering with an aeronautical emphasis. His next step: moving to Sacramento, Calif., and joining Aerojet, a California-based company that made rockets and missiles, just as the Space Race heated up.

“It just all came together at the right time,” Henry laughed. “It was kind of fortunate that I just happened to be there when I did.”

He headed up a mechanical design team that ended up working components for rocket missiles. When the government put out RFPs for its moon missions, he recalled Aerojet kept losing out on the bids to larger companies, such as Rocketdyne.

“We bid on the engine to land them on the moon and to bring them back. We called it the Moon Lander,” said Henry.

At the time, he said everyone hoped that they would be able to beat Russia and put a man on the moon first.

“The damn Russians,” Henry scoffed. “They were the first to put a satellite in orbit. They had actually made a shot at the moon, but didn't land.”

The logistics of putting astronauts on the lunar surface were more complicated.

“In general, the answers were, ‘I think we can do it but it's going to be very iffy." A lot of things have to work right. It was like, ‘Well, uh, yeah, maybe,’” Henry said. “Of course, we didn't want to tell the astronauts that. They needed more than maybes. They wanted to come home.”

They got a test run in May 1969 when Apollo 10 launched and the crew of Gene Cernan, Thomas Stafford and John Young successfully returned to Earth. Henry recalled the phone call he got days later.

“It wasn’t my boss. It was the boss’s boss. He said, ‘We’re getting together to review Apollo 10.’ I get to the plant and there’s about 50 of us in the room. The president of the company that owns Aerojet is there and I think, ‘Wow.’ For him to be there, I knew something big was coming down,” he laughed.

Henry was right. After thanking the staff for all they’d done to help the astronauts get home safely, the company’s president told them there were a couple people who wanted to say something.

“The door opens up and the three astronauts walk in,” Henry said. “I got to meet each one of them. Nice guys, they were. Really nice.”

Just a few months later, as the American public anxiously watched the Apollo 11 crew attempt something no other man had, the staff at Aerojet was on pins and needles.

“We were all just tuned in to every bit of information we could get our hands on. We had TVs all over,” he remembered. “The whole plant just essentially shut down to watch the launch and watch them land on the moon.”

Then came that first step and those first words: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

“We had a whole room full of people when that happened. It was just an uproar. I tell people, you probably could have heard us up here from Sacramento,” laughed Henry. “Pandemonium was what it was, but it was an exciting time.”

The excitement didn’t end there. Aerojet was also involved in the Apollo 13 mission. It had created the RCS thrusters on the Moon Lander, which the crew used to get home safely.

Those were the good times, but by 1972, Henry told me he saw the writing on the wall. America had won the Space Race and the companies that had ramped up efforts to get us there didn’t need all those employees anymore. Aerojet, at the time, had about 20,000.

“I had almost thirty people working for me and my big job became figuring out who to lay off next as the industry shrunk back,” he said. “I finally decided I wasn’t really cut out to do that. That's when I started looking for other things.”

“Other things” led him back home to Umpqua and the family ranch, where his life took another unexpected turn. He decided to try his hand at growing wine grapes in the Umpqua Valley, which has a climate similar to France’s Burgundy. He planted 12 acres of vineyard in 1972, but wasn’t pleased with the results. The grapes were prone to rot, given the region’s gray skies and rain.

He stumbled on a solution in 1982: splitting the canopy, thereby exposing the fruit to more sunlight and producing better quality fruit. That’s how he created the Scott Henry Trellis System, now a popular method of grape-growing used worldwide.

“It has been an interesting life, but it was being at the right place at the right time. And I don't know how that all happens,” Henry said. “It's providence, it's the way things are. Somebody's pulling the strings up there and knows a lot more about it than we do.”

He’s been at the helm of Henry Estate Winery ever since, producing award-winning wine in the heart of the Umpqua Valley. In 2012, Henry was inducted into Oregon State University’s Engineering Hall of Fame, which recognizes alumni who used their degree to pioneer creative opportunities and launch a previously unimagined career trajectory.

Henry was the product of an era during which Americans were encouraged to dream big -- to the moon and beyond. He did. And in the process, he and his thousands of coworkers helped create history and a moment celebrated even 50 years on.