HOUSTON – Fifty-five years ago, America began integrating its public schools. It was a dangerous time.

Desegregation happened because parents, including a grandmother who now lives in Houston, allowed their children to be test cases.

Now, for Black History Month, you can see a historical exhibit that tells this story through her family’s eyes at Spring Branch ISD’s Altharetta Yeargin Art Museum.

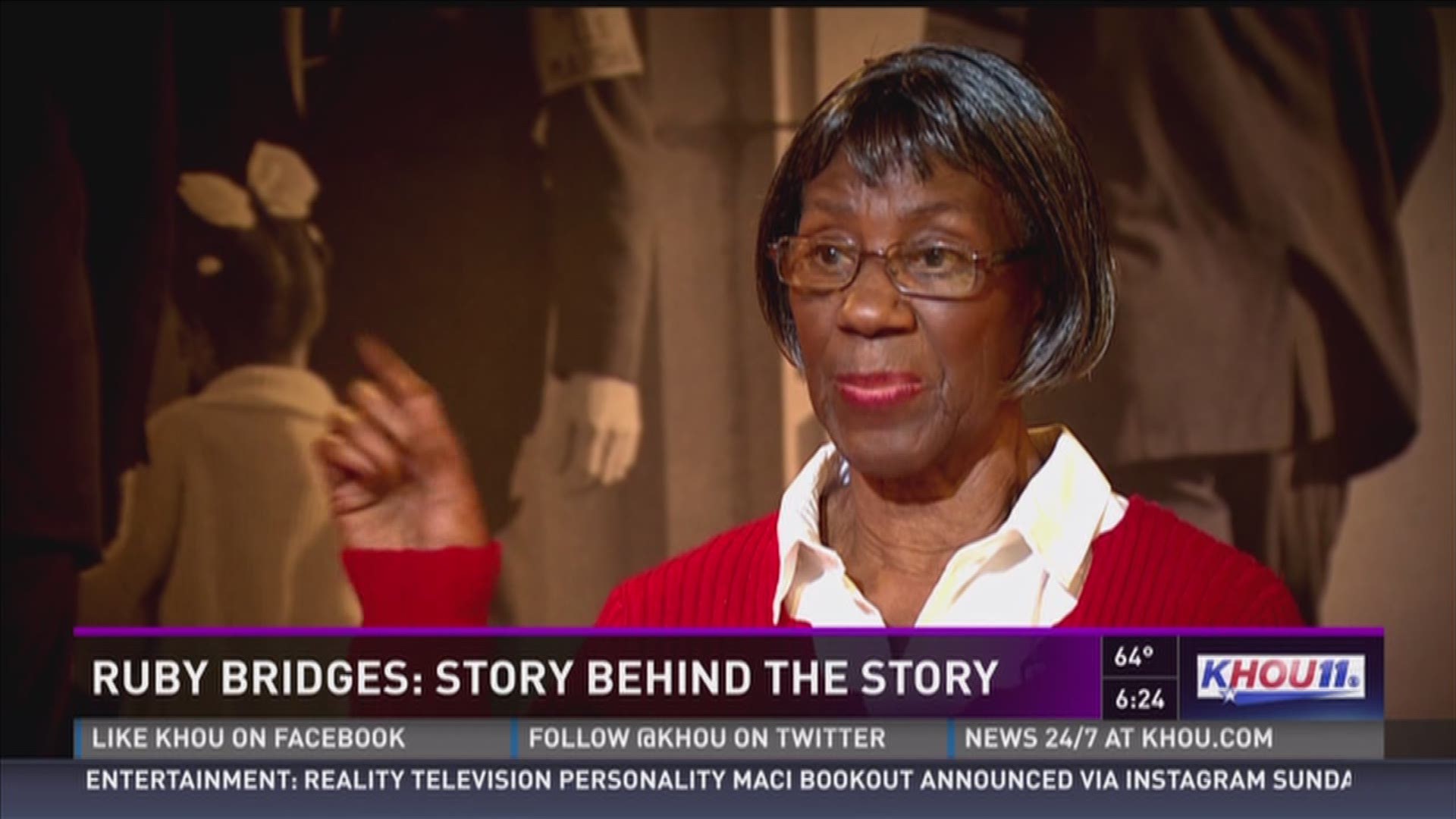

That mother, Lucille Bridges, is also making appearances to give visitors a living history lesson.

In 1960, Lucille Bridges' daughter Ruby, was the first black child to enter a white school in New Orleans. Lucille remembers crowds lined the streets to the school, shouting, “’2-4-6-8 we don’t want to integrate. Negro go away.’ Throwing tomatoes, eggs, whatever they could get their hands on.” Ruby was just 6 years old.

On this day, Miss Bridges gives a personal tour at the visiting exhibit at the Altharetta Yeargin Museum.

Armed federal marshals took Ruby to school, every day that first year. Lucille says, the Marshals said, “Don't trust no city policeman ‘cause they had children in the school theyselves.”

Parents pulled their children from the school. When some slowly returned to campus, no other children would be in the same class as Ruby. Death threats were open, terrifying little Ruby. One panel in the exhibit shows some of those threats including a woman who’d said, “I am going to poison you. I will find a way.”

Ruby was so afraid, she threw out her lunch at school. Lucille says, “She wouldn’t eat nothing but something from the store she had to open herself, like a bag of chips. She was really afraid.”

The stand also cost Ruby's father his job at a service station. A few years earlier, Cpl. Abon Bridges was fighting another war. Lucille recalls, “He fought side by side (with whites) and his best friend was a white boy.” She proudly points to a medal in a case, saying, “This is the Purple Heart he earned, in Korea whenever his friend got his leg got blowed off.”

Abon, also wounded, had put down his rifle and carried his friend to a helicopter.

Why did Lucille stand firm? Lucille says, “When I was 15 years old, I used to pick 300 pounds of cotton a day.”

She grew up in Mississippi, as a sharecropper. She couldn't go to school as long as there was work in the fields.

Lucille says, “I'd have tears in my eyes. I’d cry many a day. I'd ask God why we couldn't (go).”

She is also furious when children today waste the chance she fought to give them.

“When I see ‘em fooling around, yes, I get very angry,” she said. “I tell ‘em they can grow up to be president, doctors and lawyers.”

America might not have a black president, but for what she did.

“I think I really helped to make it happen that way,” she said.

Little Ruby challenged America's peaceful image of itself. The famous Norman Rockwell painting, “The Problem We All Live With,” shows Ruby, flanked by Marshalls against a graffiti painted, tomato splattered wall.

Looking at a print hanging in the exhibit, Lucille smiles and says, “I one of the original ones at my house.”

With all that Lucille and her family endured, it is clear that she is not at all a bitter woman. Lucille laughs gently saying, “God takes care of you. No sense in being angry with ‘em. You just hurting yourself.”

At 81, Lucille is still teaching us lessons.

Lucille is still in touch with Ruby's teacher from that first year, Miss Henry and a surviving federal Marshal, who is now 95.

The exhibit, courtesy of the Children’s Museum of Illinois, runs through March 2. Admission is $5. Lucille will be speaking Saturday, Feb. 20, noon to 1 p.m. and Monday, Feb. 29, to 7 p.m.

![inspirational stories widget [embed : 76407236]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

![635911208809279390-Ruby-Bridges.JPG [image : 80396416]](http://cdn.tegna-tv.com/media/2016/02/15/KHOU/KHOU/635911208809279390-Ruby-Bridges.JPG)

![635911209593216655-Ruby-Bridges-2.JPG [image : 80396422]](http://cdn.tegna-tv.com/media/2016/02/15/KHOU/KHOU/635911209593216655-Ruby-Bridges-2.JPG)