TEXAS CITY, Texas — Miles inland from Galveston’s beaches and colorful vacation homes, a group of Black men dribble and jump on a covered basketball court, aiming for a chain-link net.

Carver Park in Texas City, created during segregation, is considered the first African American county park in the state. It sits on land donated by descendants of freedmen who survived slavery and pioneered one of Texas’ oldest Black settlements, the footprint of which sits just a few blocks away.

Until last year, the park sat at the heart of Galveston County’s Precinct 3 — the most diverse of the four precincts that choose the commissioners court, which governs the county along with the county judge. Precinct 3 was the lone seat in which Black and Hispanic voters, who make up about 38% of the county’s population, made up the majority of the electorate.

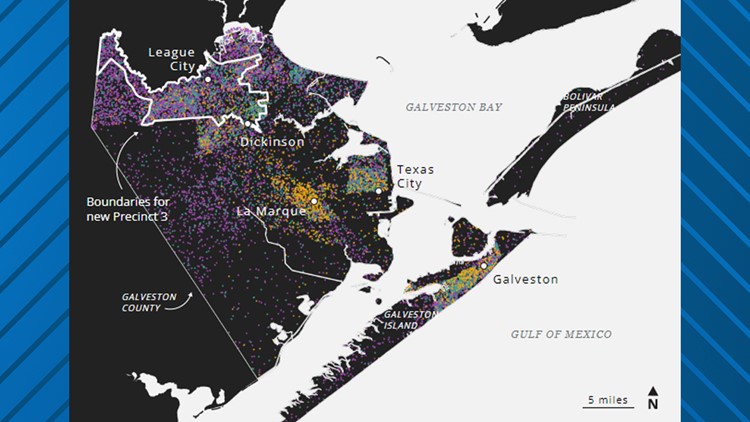

The precinct sliced the middle of coastal Galveston County, stretching from the small city of Dickinson on the county’s northern end through residential areas of Texas City and down to the eastern end of Galveston Island. Its residents included medical professionals and staff drawn in by The University of Texas Medical Branch, petrochemical workers that operate a large cluster of refineries and commuter employees of the nearby NASA Johnson Space Center.

The area stood as an exemplar of Black political power and progress. For 30 years, Black voters — with support from Hispanics — had amassed enough political clout to decide the county commissioner for Precinct 3, propelling Black leaders onto a majority white county commissioners court. They worked to gain stronger footholds in local governments, elevating Black people into city halls across the precinct. Two years ago, they reached a milestone, electing Texas City’s first Black mayor and a city commission on which people of color are the majority.

But the white Republican majority on the Galveston County’s commissioners court decided last November to dismantle Precinct 3. Capitalizing on its first opportunity to redraw commissioner precincts without federal oversight, the court splintered Black and Hispanic communities into majority-white districts.

Under the final map, which will be used for this year’s election and possibly for a decade, white voters make up at least 62% of the electorate in each precinct, though the county’s total population is only about 55% white. Because white voters in Galveston — like Texas generally — tend to support different candidates than Black and Hispanic voters, the map will effectively quash the electoral power of voters of color.

The new map was so egregious to officials at the U.S. Department of Justice that it prompted the department to file its only federal lawsuit at the county level in the entire nation challenging a redistricting plan as discriminatory.

Black residents here have often needed federal intervention to help them pursue equality and fairness. Without it, it’s possible the white power structure will never voluntarily grant them political equity and would continue threatening the gains they’ve achieved over the last few decades.

“With the district, people feel that they have a voice and a choice. Without it, no voice, no choice,” said Lucille McGaskey, a longtime Galveston County resident whose community in the city of La Marque was drawn out of Precinct 3. “It’s a shame … that it has come to people trying to wipe other people out.”

Fighting the past

Galveston’s ignominious racial past looks over the shoulders of the tourists and passersby traversing The Strand, a street of historic Victorian-style buildings just off Galveston Bay.

An imposing 5,000-square-foot mural, completed just last year, depicts the long journey from slavery to freedom that runs through Galveston. Known locally as the Juneteenth mural, it covers the side of a building overlooking the spot from which a Union Army general issued the order in 1865 that led to freedom for a quarter-million enslaved Black people in Texas, among the last to be freed after the end of the Civil War.

Galveston’s dreams of greatness in those days rested on its access to the water and proximity to cotton fields, and it boomed as a trade gateway for Texas and the Southwest. In recent years, historical markers have been added along The Strand to more fully recognize that those economic aspirations depended on the dehumanization of people kept as slaves.

The markers and the mural are symbolic, though they offer those with long ties to the area a more official — or at least public — acknowledgement of this community’s history and the way Black residents still find themselves fighting the past.

Though he’s a product of Galveston County, Commissioner Stephen Holmes did not initially grasp the significance of Precinct 3 to the community when he was suddenly appointed to the job in 1999 after the previous commissioner died. A prosecutor by trade, he inherited the seat from Wayne Johnson, who had become the county’s first Black commissioner in 1988.

Once in office, Holmes was struck by the intense pride his constituents took in Precinct 3, the ultimate spoils of a yearslong struggle to build coalitions, often assisted by federal intervention to protect voting rights. Early in his tenure, he met older voters who were the grandchildren of people who had been held as slaves. Some of his constituents had participated in sit-ins, paid poll taxes, attended segregated schools and lived through a long stretch during which their voices were shut out at the highest level of local government.

“This is a 1960s-style fight for democracy,” Holmes said from his precinct offices housed in an old Wal-Mart building turned government complex in Texas City.

Holmes — who is Black, the only Democrat on the commissioners court and the only one who is not white — said it’s impossible for him to win reelection when his term is up in 2024 given the new Republican map dissecting his precinct. He sees the effort not as an indictment of his public service but a repudiation of his constituents.

During his time in office, Holmes has grown accustomed to being on the losing end of 4-1 votes — the sole foil to the court’s Republican majority. But he has at least captured the voices of his constituents on agenda items that have recently included a local disaster declaration regarding the border, which is 400 miles away, and putting COVID relief funds toward building a border wall. He was the lone dissenter to keeping a Confederate statue on the grounds of the old county courthouse.

He has also built strong ties with his constituents in moments of both joy and despair.

Holmes proudly displays in his office a large panoramic photo of a jubilant crowd at one of the annual barbecues he hosts. The soiree is a community staple and highlight for some of the older, mostly Black residents who typically attend. In recent years, the event has included dance performances by some of those residents who dub themselves the “Stevettes.”

The photo hangs over a waiting area Holmes and his team used as a makeshift FEMA help center in the wake of Hurricane Harvey’s destruction when his constituents faced hourslong wait times to request assistance through the federal agency’s disaster phone line. Holmes set up county laptops so his constituents without computers or internet could access a FEMA website and he helped figure out transportation for those who couldn’t get to his office on their own.

Republican power play

Set back behind a row of massive crepe myrtle trees with thick trunks that, like the rickety shiplap of nearby houses, are showing their age, the old entrance of the “Colored Branch of Rosenberg Library” sits on a quiet street near downtown Galveston in a portion of the island that used to fall within Precinct 3.

Given its proximity to her home, Sharon Lewis has had to explain the significance of the relic of segregation to her granddaughter, using the same refrain she uses to describe historical inflection points to her — “a moment in history.”

Lewis was among the last to speak of the roughly 40 mostly Black residents who packed the November meeting to vociferously oppose the court’s redistricting plan. Just two people testified in support. Pastors, local officials and longtime residents took turns admonishing the court for dismantling Precinct 3, leaving hardly any room for them to participate in the process and turning back the clock on their representation. The ordeal was in some ways a preview of what they feared will result from the county’s mapmaking — that they will no longer have a voice.

The events leading up to commissioners’ vote on the map had proved to be a bold exercise of Republican power wrangling.

The proposal was placed on the court’s agenda on the last day by which the county could make changes before the March primary election. The meeting — the only one allowing public testimony on the proposal— was scheduled for the middle of a workday in an annex building at the county’s edge instead of the larger county courthouse. The room was so small that only two commissioners and County Judge Mark Henry fit on the dais; Holmes sat at a small white table down in front of them.

Scores of residents showed up and many were left in the hallway straining to follow the proceedings or hear their names called to speak.

When people complained they could not hear, Henry tersely responded that the room did not have microphones and he wasn’t going to shout. When the crowd collectively scoffed at his remark, he threatened to clear them out if they made noise.

“I’ve got constables here,” said Henry, who did not respond to multiple requests for an interview for this story.

Henry and the other commissioners did not address any of the public’s concerns, except to say there was no time to consider anything except two proposals drawn up by a Republican consultant — both of which upended the boundaries of Precinct 3.

Just before the court’s vote, Holmes held the floor with an attentive audience that hummed in disapproval as he detailed the chicanery of the Republican maneuver.

There had been no criteria adopted to guide the redistricting process, the only commissioner elected by Black and Hispanic voters was largely shut out of the process and the opinions of those testifying were being cast aside.

The crowd was cheering by the time Holmes pronounced they would not “go quietly in the night.”

“We’re going to rage, rage, rage until justice is done to us,” Holmes said.

The court passed its new map on a 3-1 vote (one commissioner was absent) and quickly adjourned. The other two commissioners who voted for the plan, Darrell Apffel and Joe Giusti, also did not respond to requests for comment, though Henry and Apffel have been quoted in the local newspaper arguing that the redistricting plan will benefit the county by consolidating its coastal areas into one precinct.

Under the county’s new map, most of Precinct 3 was cracked in three ways, significantly reducing its footprint to the whiter northwest portion of the county and shrinking its share of Black and Hispanic voters by 28 percentage points. Holmes’ former constituents in more diverse pockets of the county were split across the four precincts.

After the hearing adjourned, those who had gathered joined hands and transformed the ordinary government meeting room into a protest venue with a rendition of “We Shall Overcome.” Recalling that moment, Holmes noted he had sung those words many times throughout his life and certainly since taking office, including at events commemorating Black history. But he realized he had never personally taken on their weight the way activists and protesters did when they lifted the song up as a civil rights anthem.

“I will tell you that that may have been the first time that I really felt it in my soul, about what people during the civil rights movement felt when they were singing those songs,” Holmes said.

The Justice Department’s lawsuit landed four months later. In a complaint filed in federal court in Galveston, it argued the map was discriminatory because it denied Black and Hispanic citizens an equal opportunity to participate in the political process.

“The way I think about this is that there’s been a consistent battle in Galveston for decades over ensuring fair representation for Black and brown communities,” said Hilary Harris Klein, a senior counsel for voting rights with the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which also sued the county over the map on behalf of three local branches of the NAACP and a local LULAC chapter.

(The county has not yet formally addressed the legal issues raised in the lawsuits, which both claim the court ran afoul of the federal Voting Rights Act. Instead, the county asked for a postponement in the case until possibly 2023 while the U.S. Supreme Court considers a challenge out of Alabama that could further contract the Voting Rights Act’s protections from discrimination in redistricting.)

The redraw of Precinct 3 likely would have been blocked under federal oversight — known as preclearance — that existed before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County vs. Holder, which dismantled the law designed to shield voters of color from being robbed of political power.

A lynchpin of the Voting Rights Act, the oversight, covered states like Texas with long histories of discrimination and required changes to elections and voting maps to clear federal reviews before taking effect.

That protection proved crucial in Galveston’s redistricting a decade ago when the commissioners court similarly attempted to reconfigure Holmes’ district but were blocked by the Justice Department. The court backed away and Precinct 3 was preserved.

But preclearance was gone by last year’s redistricting work, the first time in nearly half a century that lawmakers, both at the state and local level, could redo political maps without federal supervision. Freed from review, the Galveston County commissioners — led by the same county judge from a decade before — made good on their previous effort.

“That is something that the powers in play have been trying to do for a very long time and with the Shelby decision and with the dismantling of preclearance, they saw that as a tacit permission to do so,” Harris Klein said. “Galveston is really emblematic of what’s happening across the South post-Shelby. We’re seeing the biggest regression in minority rights since the Voting Rights Act was passed.”

Across the country and in Texas, Republicans are using the latest round of redistricting — and their new freedom — to preserve the GOP’s political dominance and cement their power even at the cost of communities of color.

In Galveston, the impending elimination of Holmes as the only Black commissioner echoes efforts in other parts of the country where the districts of Black elected officials from the county level to Congress are being chipped away in maps that erase decades of electoral gains by the voters of color. Just this week, though, Henry appointed Robin Armstrong, a Republican local doctor who is Black, to finish out the term of the county’s fourth commissioner, who recently died.

Anger and disappointment

The two legal cases against Galveston County are now at the start of what’s expected to be a drawn-out stay in federal court, but locals fear the fight could determine more than just the fate of Precinct 3.

In between the commissioners court’s decennial efforts to pull apart the precinct, the communities that comprise it have been quietly working to harness the power of their votes. In 2020, the voters of Texas City elected Dedrick Johnson, making him the city’s first Black mayor. He governs the heavily industrial city of 50,000, where Black and Hispanic residents account for roughly 60% of the population, along with a city commission of six members — four of whom are people of color.

Johnson ran unopposed for reelection this year. But in describing the fallout of dismantling Precinct 3, many residents wonder how long those gains can be maintained when the message Galveston County voters are receiving through the county is that their votes don’t matter.

From his desk behind the midcentury modern facade of city hall, Johnson said he understands those fears, especially given the treatment Precinct 3 residents received at the commissioner’s November meeting when they faced what he described as an “arrogant display” of disregard for their voices.

“One of the things that is a core tenet of the elected official is you are elected by the people to work for the people, and when you silence the voice of the people then one is unsure that those who are elected will actually do what they say they’re going to do,” Johnson said. “And if that [November meeting] is any indication of the representation that those people will subsequently get from this redistricting, then it confirms their anger. It confirms their disappointment.”

Others are bracing for what the devaluation of Black and Hispanic votes in the county will mean for efforts to bring more people into the electoral process.

That’s the mission community activist Roxy Hall Williamson has adopted since returning to Galveston Island a few years ago. She traces her ties to Galveston back to her grandmother who was a nurse there and her grandfather who worked as a ship’s cook. Williamson was born on the island, and her mother moved her family away when she was a child but she returned every summer.

Once her daughter graduated high school, Williamson returned to Galveston permanently. After attending a political event, she started seeking out opportunities to organize and has more recently been working to establish a local voter advocacy group through which she wants to create a suite of voter education tools, hoping to pass down voting literacy in the way some families pass down generational wealth.

But these days, Williamson grimaces at how she’d even convince someone to register to vote once they’ve heard the news of the new county map.

“It’s almost going to suck all the air out of it,” she said.

Williamson proudly shepherds out-of-town visitors to the Juneteenth mural in Galveston to share her community’s truth. She helped organize the turnout at the commissioners court’s November meeting, but when she walked out of the crowded room once it adjourned she realized how much the present was echoing the past.

Feeling that the Black people of Galveston County were again in need of protection from discrimination by their own government, she pulled out her cellphone and dialed the Department of Justice’s civil rights hotline.

“What did it all mean if they can just take it away?” Williamson said.

This story comes from our KHOU 11 News partners at The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans - and engages with them - about public policy, politics, government, and statewide issues.