Under the scorching Texas sun, an older man dressed in a white t-shirt and khaki shorts pulls a long green hose across his front yard. Birds chirp a midday song. A power saw roars in the distance. Water sprays from the end of the hose, soaking his neatly manicured lawn that shows no ill effects of the historic flooding that drowned his Bear Creek Village neighborhood nearly a year ago to the day.

A house across the street tells a different story. The outside of the red-brick colored home is cluttered with overgrown grass and bushes. Grime-stained window panes show a two-foot-high water mark that provides a foggy view inside a home that sits bare down to its studs.

It’s been a year since Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, a historic storm that dropped a trillion gallons of rain across the 1,700 square miles of Harris County—enough to power Niagara Falls for 15 days.

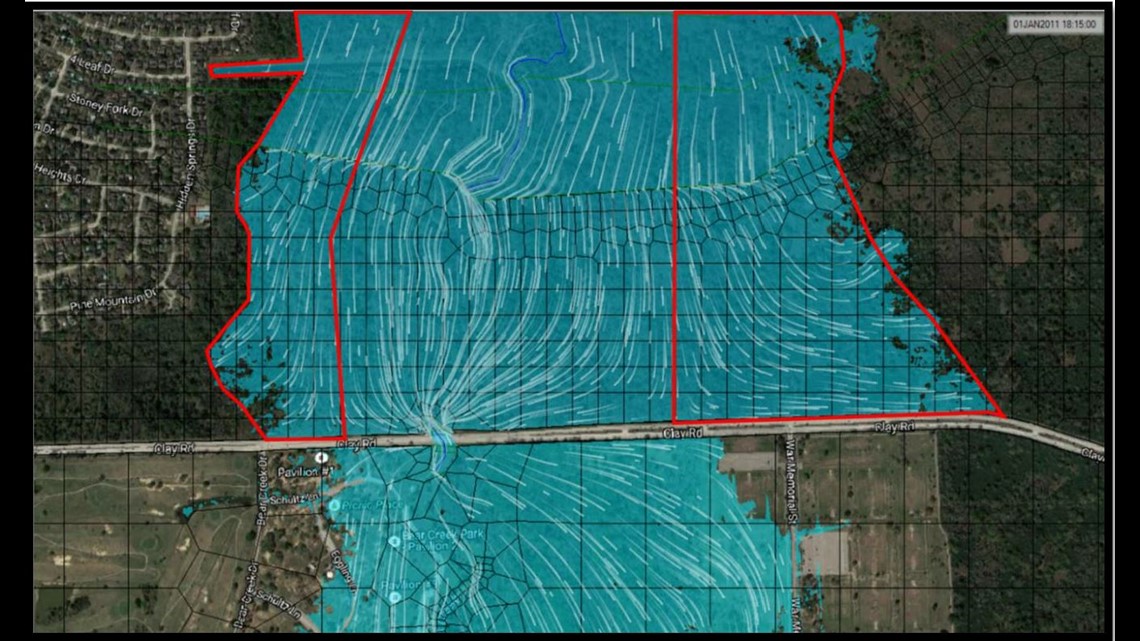

In Bear Creek Village, 65 percent of the neighborhood’s 1,900-plus homes flooded during Harvey, according to the local homeowner association. In the eastern end of the neighborhood, where Langham Creek feeds into the Addicks Reservoir, some homes saw upwards of six feet of water inside.

It was one of the hardest hit areas during Harvey.

For many residents, it wasn’t the first time they flooded.

Some homeowners, like Shelly Schmitz and her family, decided to stay and rebuild. Schmitz, who’s lived in her home for 22 years and has flooded twice, couldn’t leave the comfort of the neighborhood where her kids grew up.

“We don’t want to start over in another neighborhood,” Schmitz said. “This is where we want to be.”

Other families, like Jim Yuhnke and his wife, have flooded three times in the past 10 years, including Harvey. They took their insurance money, sold their home and found a house on higher ground three miles away. Three floods were too many.

“One of the reasons we moved is because I think it’s going to flood again,” Yuhnke said. “They haven’t done anything to stop it from flooding.”

Then there are families who walked away altogether, some of whom didn’t have flood insurance, left to start anew after Harvey destroyed all they owned—from their clothes in the closet to their cars in the garage.

Now residents—those who have returned—are demanding action. The rebuilding process too fresh; the next storm coming too soon.

Longtime resident Bill Cook is spearheading those efforts by rallying residents to join a campaign to send letters to elected officials on the local, state and federal levels. Cook, who’s lived in the neighborhood for 39 years, had 16 inches of water flood his home. He and his wife live in a modest three-bedroom, two-bathroom brick home that sits in the neighborhood’s east side. It took eight months to rebuild. They don’t want to do it again.

In those letters, residents voice their concerns about what they feel is exacerbating the flooding in their neighborhood: an overgrown and debris-filled Langham Creek, which runs adjacent to the neighborhood; the Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE), which owns the land in Addicks and Barker reservoirs, is stymying local efforts to reduce flooding; and a bridge that doesn’t allow water to adequately flow through from the north side of the reservoir to the south.

That bridge tops the list of residents’ concerns.

In the early 2000s, the city of Houston annexed a portion of Clay Road in the reservoir. Back then, that portion of Clay Road was a narrow, heavily trafficked two-lane road that often flooded during heavy rains as water flowed downstream into the reservoir.

The city raised the road, added a lane to each side, a median and built the bridge. What prevented the flood-prone road from flooding had unintended consequences: during heavy rains, the bridge doesn’t allow enough water to pass underneath into the rest of the reservoir, creating a dam effect that can cause water to backflow into Bear Creek Village.

“We’re being flooded by a city bridge that was poorly designed and inadequate,” Cook said. “Shame on them for building that bridge the way they did.”

Among residents’ frustrations is that the city-owned bridge sits in an area that is otherwise widely unincorporated Harris County, meaning there’s no city voters. Houston’s District A weaves through various streets off Clay Road but doesn’t include any of the surrounding neighborhoods.

Residents feel their concerns are falling on deaf ears at the city.

Steve Costello is the city’s chief resilience officer who’s better known locally as Houston’s flood czar. As such, he’s tasked with developing strategies to reduce the severity of flooding in the city. Costello said he’s aware of the problems posed by the Clay Road bridge. Action hasn’t been taken, he said, because of a pending study by the Army Corps of Engineers that would look deeper into issues with the reservoirs. (A spokesperson for the ACOE said the Corps is waiting for $6 million in funding for that study to come in and “we expect to have a recommendation of alternatives in four years.”)

That timeframe doesn’t sit well with residents, some of whom have flooded two or more times in the recent years.

“Waiting for yet another study is not going to go over very well as houses flood,” Cook said.

Costello stressed that the city “is committed to helping in all areas where we have issues in terms of impacts of flooding and draining.”

After the 2016 Tax Day floods flooded nearly 300 homes in Bear Creek Village, Matt Zeve, the director of operations for the Harris County Flood Control District, commissioned a study to evaluate the effects of the bridge and determine alternatives solutions that would allow more water to pass through.

That study mirrored what residents said they knew all along: the bridge is enhancing flooding in the neighborhood.

The study provided alternative solutions on how to alleviate the damming of water. Those solutions include adding culverts at strategic locations along Clay Road to building a new bridge altogether. It all comes with a cost, and as Zeve said, “a lot of times that’s what drives is cost.”

Rough cost estimates provided by the study range from $1.5 million to install 20 culverts to $8.4 million to build a new 70-foot bridge.

“The smartest thing to do is build a new bridge,” Zeve said. “Bridges, if you build them right, they last 50 years. And that’s the smartest thing to do; it’s the longest-term solution.”

The problem with building a new bridge is the time it would take to build. Zeve said a new bridge would take Clay Road out of commission for up to a year; adding additional culverts could take about a week.

The issue comes at a time when the Harris County Flood Control District is holding an election on a proposed $2.5 billion bond that would go to addressing flooding issues throughout Harris County.

Zeve called the Clay Road bridge project low-hanging fruit, in that a study is already complete and moving forward would only require working with the city to select one of the proposed alternatives before handing the project off to the city. Because the bridge is city owned, the city must manage the project and construction.

“This is one of those projects that can make a difference and also give these people in Bear Creek Village a sense that we do listen to them and give them a sense that their concerns are being addressed,” Zeve said.

If the proposed bond were to pass, Zeve said the flood control district would happily finance most—if not all—the project cost.

Because the bridge is on federal land, the ACOE must sign off on all proposals and issue permits before any construction can begin. It’s another frustration added to long list of others for the residents of Bear Creek Village who are fed up with bureaucracy, inaction and flooding.

Almost a year after Harvey, the neighborhood is still on the mend. While some—like the man watering his manicured lawn—have rebuilt, others live with dumpsters in driveways and inside camper trailers parked in front of their homes in hopes of returning to normal life.

A normalcy that, for many, still feels uneasy. The fear of future flooding is never far from the front of their minds.