HOUSTON — On this very day, April 10th, 1912, the most famous ship in history set sail from Southampton, England as the clock struck noon. With full pomp and circumstance, the grandest, biggest ship the world had ever seen, gracefully slipped away from its moorings at Pier 44. In four short days, the dreams of many would turn to nightmares thanks to a bout of arrogance and an iceberg.

It was an routine, uneventful journey up until Sunday night when the crows nest lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee spotted a massive iceberg looming in the distance and quickly rang the bell and phoned the bridge. After reversing the engines and turning the ship hard to starboard, the ship clipped the berg on its starboard side at precisely 11:40 p.m. Two and a half hours later at 2:20 a.m., the great ocean liner would sink into the perfectly still and icy waters of the north Atlantic.

While its understood that the weather on the night of the sinking was calm, clear and cold, it was very likely those conditions that set the course of history and sealing the Titanic's fate.

The weather was unusually calm that night with the surface of the ocean completely still. The captain of the Titanic, Edward J. Smith, was quoted as saying ''it was like a mill pond,'' which was reflected in the 1997 blockbuster hit "Titanic."

The lookouts along with the officers on the bridge knew that a calm ocean would make icebergs hard to see with no breaking water at the base. It was also extremely cold that night with sea surface temperatures reportedly at 28 degrees -- a lethal temperature for any person.

Climatology would suggest that the area several hundred miles southeast of the Grand Banks would be far warmer in mid April than what was experienced on the night of the collision.

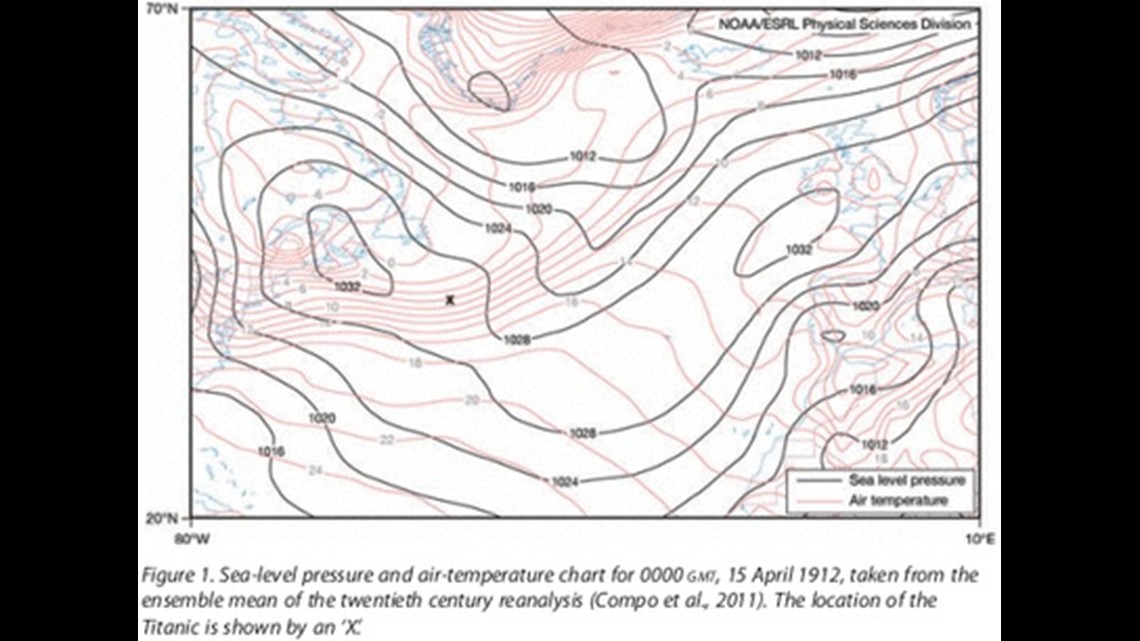

According to the Royal Meteorological Society a large high pressure cell over the central Atlantic had persisted for weeks keeping a perpetual north and northwest wind over the area of the North Atlantic that not only drove icebergs much further south than normal in April 1912 but also drove bitterly cold air south out of northeast Canada into the main shipping lanes.

That large high pressure cell not only explains why it was so cold that night but also why the weather was so clear and the seas so calm and the water so deadly cold.

All together, the weather, on a moonless night, condemned a ship that was said to be unsinkable. While many of the ill-fated passengers survived the initial sinking of the great ship itself, it was the icy waters that snatched the life out of those bobbing in the sub-30 degree water. One by one, with half-empty life boats floating near by, hypothermia helped to manufacture one of the greatest peace-time maritime disasters to date.

Had the Titanic sank in a more tropical environment with warmer waters, the loss of life would have been far less.

Not long after the Titanic sank, the HMHS Britannic, the third of the Olympic-Class liners built by White Star Line, struck a German mine in the Mediterranean Sea and sank within 55 minutes compared to the 2.5 hours that it took the Titanic to sink. Yet despite the fast sinking, of the 1,065 passengers on board only 30 died. This is credited with 70 degree water versus 28 degree water where Titanic was, more lifeboats (installed by White Star Line after the Titanic disaster) and a faster arrival of rescue ships.

While sometimes being an after thought, weather has played a pivotal, crucial role in many storied disasters from the Titanic to the Hindenburg to the Space Shuttle Challenger. It's the lessons learned from past tragedies that continue to keep us mindful of what can happen when Mother Nature is challenged.