This story is part of KHOU 11 Investigates' series “Unforgivable.” Parts may contain graphic descriptions of sexual assault. If you or a loved one have experienced sexual abuse, get help through the free and confidential National Sexual Assault Hotline (1-800-656-HOPE).

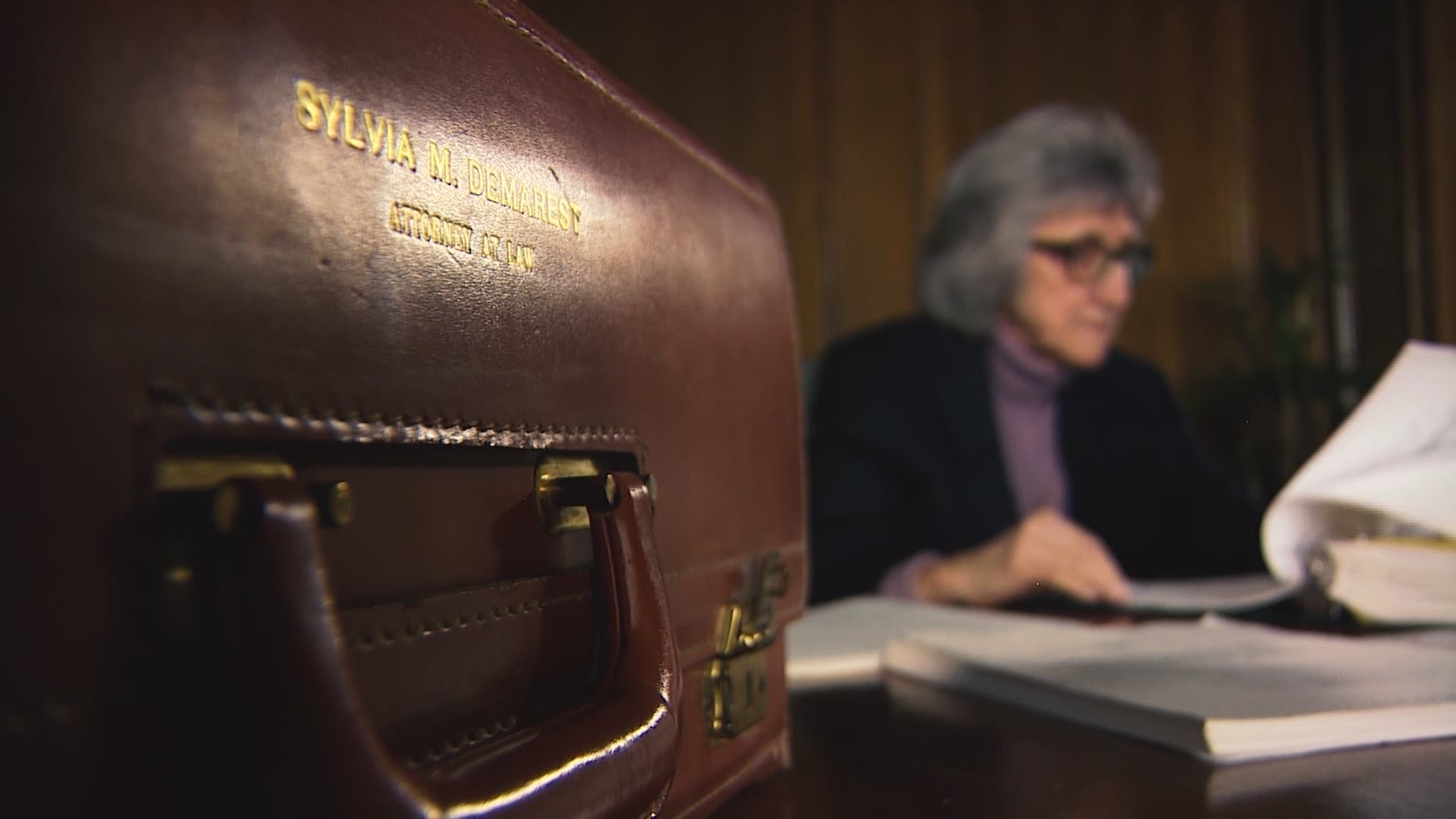

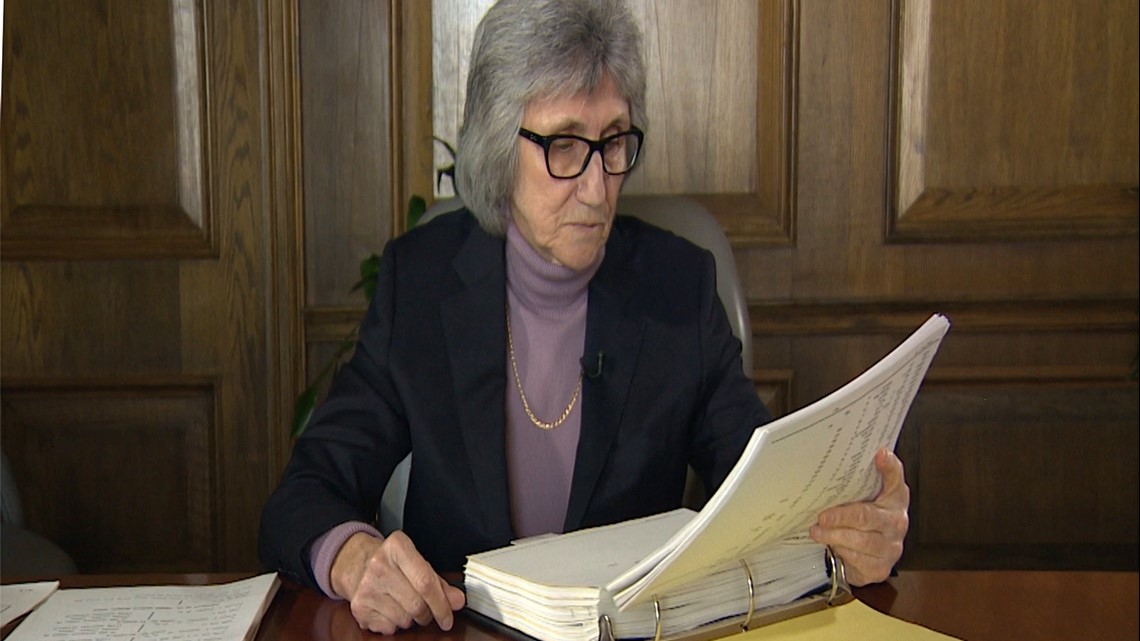

The thick, black three-ring binder filled with hundreds of small-type pages looked like any other dry document belonging to a veteran attorney.

But for Sylvia Demarest, this was no ordinary file. This was the culmination of a decade of her life’s work to expose a conspiracy of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church.

“I read everything,” she said.

“Every horrible thing that a priest had done to a child.”

Demarest flipped through the pages, running her venerable index finger across countless names and cities, Grand Rapids, Michigan; Great Falls, Montana; Gallup, New Mexico; Dallas; Houston; and Boston. Each line representing a sordid tale of thousands of priests accused of abusing children.

For decades, the now-retired attorney has lived with many of their stories of their pain, the worst moments of their lives.

Demarest first was introduced to clergy sex abuse as an attorney representing survivors around Texas and gained notoriety in 1997 when one of her cases proved conspiracy and ended in a $119 million verdict — the largest ever against the Catholic Church.

The horrors of that abuse and of the church’s complacency fueled an 11-year research project to document every public priest abuse case. The work would help start BishopAccountability.org, an online database of the sex abuse crisis.

“I’m a lawyer doing my job; that’s really the way I look at it,” Demarest said in December. “And I think doing my job, once I understood that there was a problem, doing my job included putting together this database just out of respect for my clients, if nothing else. And other survivors.”

The first cases

It started 25 years ago in a conference room and a daylong meeting with two boys, their parents and a disturbing story that only got worse as the day turned into night.

“I learned not only had the (son) they wanted me to interview had been abused by a priest but that their other son had been abused by (another priest),” Dallas attorney Sylvia Demarest said. “I was angry.”

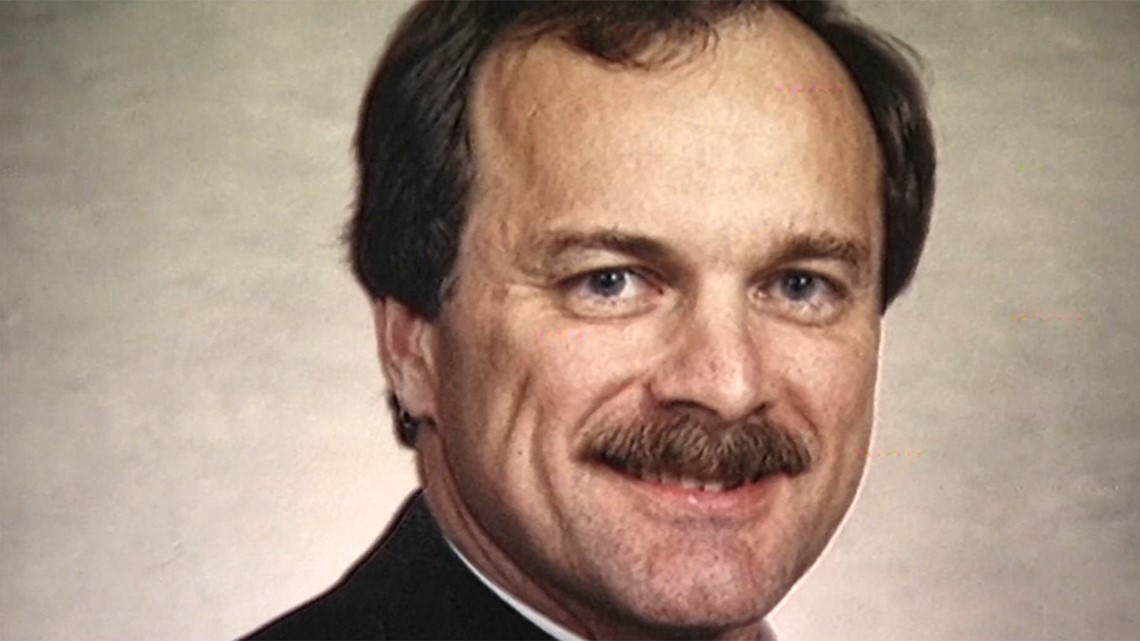

The two Dallas priests — Rudy Kos and Robert Peebles — were both sued and accused of raping boys, and Kos’ accusations were especially disturbing.

“We know the abuse ranged from everything from … oral intercourse to fondling to using their foot to satisfy and gratify themselves. The full range of what an adult can do to a child was involved in this case,” Demarest said. “Totally disgusting.”

Demarest pointed to how Kos used the same tactics as other abusers: targeting boys with absent fathers, starving for attention. She said Kos would give them presents, show them pornography and supply them with drugs and alcohol.

“He drew them all into this secrecy cult, where they had this special relationship with God through this priest, and it was very effective, both in ensuring the loyalty of the children to him and silencing them,” she said. “The boys all said, ‘We thought we had friends in high places, through Rudy Kos.’”

A priest is a direct link to God in Catholicism, and Kos used that tenet to excuse his actions, Demarest said. One survivor told her that after he was abused by Kos, the priest told him to shower, “because he blessed the water and it was holy water and it would absolve him of his sin for engaging in sexual activity.”

During the case, she learned Kos had a history of sexual abuse predating priesthood, going back to his childhood. He was sent to reform school after he was accused of abusing a sibling and a neighbor boy, Demarest said. The diocese knew about that, but it didn’t stop him from being accepted into seminary, nor did complaints from other seminarians bar him from becoming a priest, according to court documents.

At every stage, she said the diocese “failed to investigate, failed to follow up, failed to be curious about the suitability of the people that they were going to ordain in the priesthood.”

“I was so astonished by what I learned in terms of the power and complicity of this institution,” she said.

Landmark judgement

The Diocese of Dallas offered to settle the Kos case out of court, but with several strings attached, including a nondisclosure agreement and sealing the case.

“We did not want to be part of what we saw as essentially a conspiracy, to avoid public information and public knowledge of the crisis,” she said.

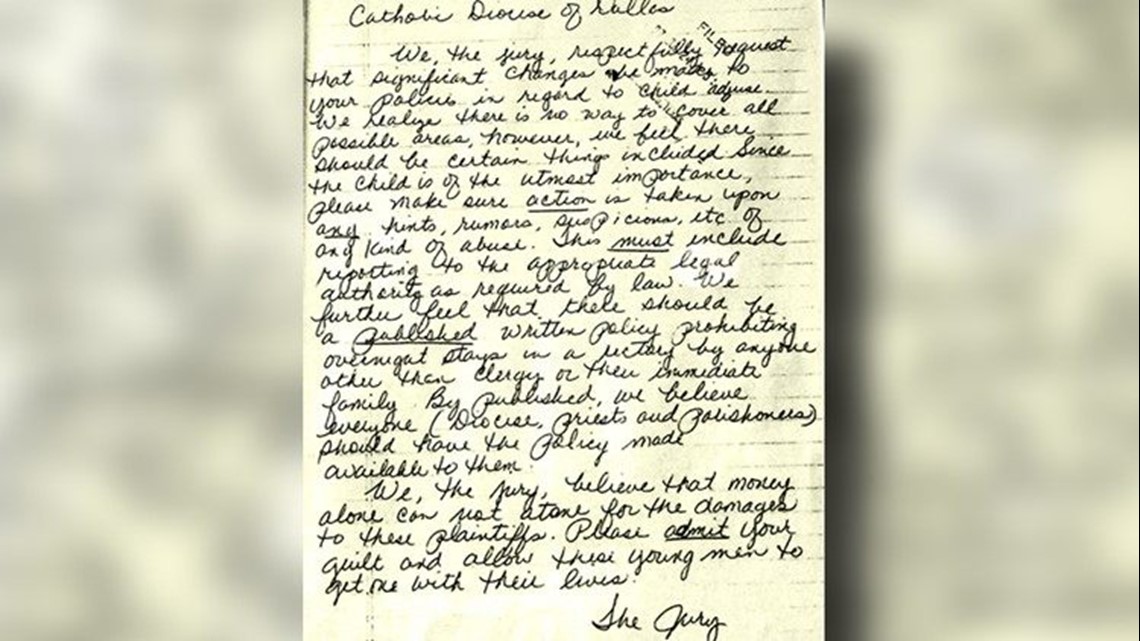

They took the case to trial, and the jury in Kos’ case agreed that the church knew Kos was a predator and should have done more. Along with the $119 million judgment they made against the church, they also wrote a letter to the Dallas bishop, demanding that he fix the problem.

The jury outlined reforms they wanted — a stronger, published written policy and a promise to take action on any “hints, rumors, suspicions, etc. of any kind of abuse,” including reporting it to authorities.

“We, the jury, believe that money alone can not atone for the damages to the plaintiffs. Please admit your guilt and allow these young men to get on with their lives,” the letter read.

There were 11 boys named in the suit against Kos. One of them committed suicide before the case was filed. Another one overdosed about a year ago. Demarest said many of the other survivors have struggled with relationships and life.

“That’s a statement to me and a testament to how damaging this was to them,” Demarest said. “It’s impossible for them to just feel normal, and there’s every reason to believe that the church knew this at a very early stage in the crisis.”

Kos was later criminally convicted and is serving three life sentences. The Peebles case was later settled out of court.

‘It was conspiracy’

After the verdict in the Kos case, Demarest made a poignant comment to reporters, “I hope this wakes up the Pope.”

The massive verdict wasn’t the wake-up call she was hoping for, but with validation of a conspiracy from a jury, Demarest dove deeper into her cases and research.

“My reaction would be, ‘I’m going to get to the bottom of this, and I’m not just going to do it in this case. I’m going to do it in all the cases. I’m going to find out what is really going on with this crisis, across the United States,’” Demarest said.

Alongside her legal assistant, the late Patricia “Trish” McLelland, they gathered all the lawsuits and press articles they could find.

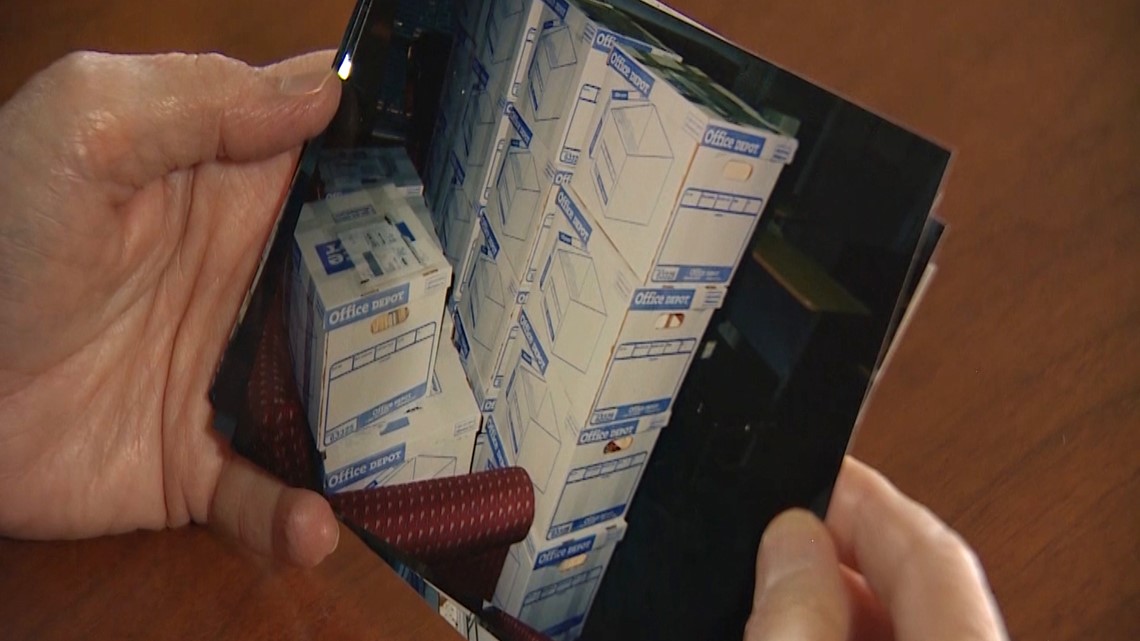

Their work turned into 2,600 names and more than 100 boxes of documents they would later ship off to BishopAccountability.org, an online database of the sex abuse crisis. The then-fledgling site has now grown to more than 6,000 names today.

“We cracked the code. No one had cracked the code. Not only did we crack the code, we put together the information to document what the code was and how it worked,” she said.

They noticed a pattern in how predator priests were handled. It was a four-step process: keep the priest active because there was a priest shortage, don’t tell the public about the allegation, don’t report to law enforcement and placate the victim.

“It was a conspiracy,” she said. “No one likes to hear the word ‘conspiracy,’ but under law, conspiracy is very simple — a meeting of the minds, certain overt acts, some of which are illegal, in order to achieve a common goal, and that goal was to make sure that the church was protected.”

Slow change

Demarest has watched the church continue to protect itself in the years since her research.

Still, she said something feels different now, and real change is on the horizon.

As of December, at least 70 of the 196 dioceses in the country have released their own list of “credibly accused” priests, according to BishopAccountability.org. Of those, only one is in Texas, the Diocese of Fort Worth.

That will change soon with every diocese in Texas planning to release a list later this month. That brings Demarest hope, but she doesn’t expect totality to come from the lists.

She knows some victims will never come forward. She believes that priests who were reported anonymously won’t be named on the list. She cited one high-ranking Dallas church official during the Kos case who told her he throws away anonymous letters.

“I said, ‘If you get ten anonymous letters about a priest what do you with that?’ ‘I throw it in the trash.’ You see the problem here?” she said.

She predicted, however, that at the least, most of the priests who were sued will appear on the lists.

“It’s a big deal. It’s a big deal for victims, it’s a big deal for the community and it’s definitely a big deal for the church,” she said. “So, they’re going to put every name they have to on the list.”

And other recent developments have given Demarest hope. The search of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston’s secret archives into a priest sexual abuse investigation in November was unheard of when Kos was arrested in the 1990s.

“They’ve never had Texas Rangers going through the Chancery. They’ve never had boxes of information confiscated. That’s completely alien to this institution,” she said. “They used to run the police. They used to run the courts.”

Even so, she said more change is needed to break the system of secrecy and the pain of her clients that she’s carried with her for decades.

Maybe, she said, a bishop may need to go to prison before the system can be broken and real change can happen.

“(Bishops) would all say that they’re only accountable to God, but that’s not true. They’re accountable to society as well,” Demarest said. “And until the civil and criminal authorities enforce that accountability, perhaps through criminal prosecution, the situation will probably not ever change.”