Charlotte-Mecklenburg Chief of Police Kerr Putney stood in a crisp white uniform, shielded by a podium.

Two days passed since CMPD police fatally shot Keith Lamont Scott, a 43-year-old black man armed with a gun. As a widow wept, as riots erupted in the streets, as the community demanded release of the officer’s body cam footage, Putney adjusted the mic.

“I never said full transparency,” Putney said. “I said transparency.”

It was a defining moment in the throes of police mistrust.

Transparency is the buzzword and body cameras the blueprint of law enforcement agencies nationwide. With the proliferation of police shootings, the rush to purchase cameras was supposed to foster accountability and insight to the truth.

Despite user-friendly technology and basic protocols, most law enforcement agencies aren’t following their policies and basic elements of the cameras, rendering their programs nearly ineffective.

INTERACTIVE MAP: Body-camera programs across the nation

A review of 62 police departments found that the four main issues surrounding the integration of body cameras fell within human error, logging issues, rush implementation and an overall lack of transparency.

Human error

The city of Oakland’s IT team accidentally deleted a quarter of the police department’s body-cam footage during a computer system upgrade.

The department didn’t know exactly how many video files were lost in the mass deletion.

“The City worked with the vendor’s experts to restore the footage,” Officer Marco Marquez said in a public statement released by the Oakland Police Department. “Unfortunately, the footage was unrecoverable. The City is not aware that this has impeded any investigations.”

That wasn’t the only error by the city. The police department purchased a backup system, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, but it wasn’t installed.

“The City then put into place a new backup system to prevent this from happening again,” Marquez said in the statement. “The City is now soliciting proposals for a new body-camera system. The City is using this opportunity to enhance its system and safeguards.”

Some departments are taking those safeguards out of officer’s control. That’s why the city of Austin equipped its officers with body cameras that automatically activate whenever the officers exit their patrol vehicles.

The lack of automatic activation, though, has been questioned with the many recent shootings nationwide. Because officers have to activate the cameras themselves, they have often missed the start of the encounter or the entire shooting itself.

In Fort Worth, a city without automatic activation, a review of 10 random officers showed they were supposed to record 93 separate incidents during two days in early August. Just 16 of those incidents were recorded -- a 17 percent compliance rate.

In New Orleans, the department compiles scorecards of how many times officers are supposed to record and how many times they actually do.

The first scorecard in May 2015 depicted a department struggling with lack of documentation with some districts failing to record more than half of all service calls. A year later, the scorecard showed NOPD officers with a 98 percent compliance rate.

The New Orleans Police Department creates monthly scorecards of body-camera compliance. In May 2015, the scorecard revealed officers failing to record when required. A year later, the May 2016 scorecard indicates major improvement—a 98 percent compliance rate—across the entire department. Use the slider to move between the two scorecards.

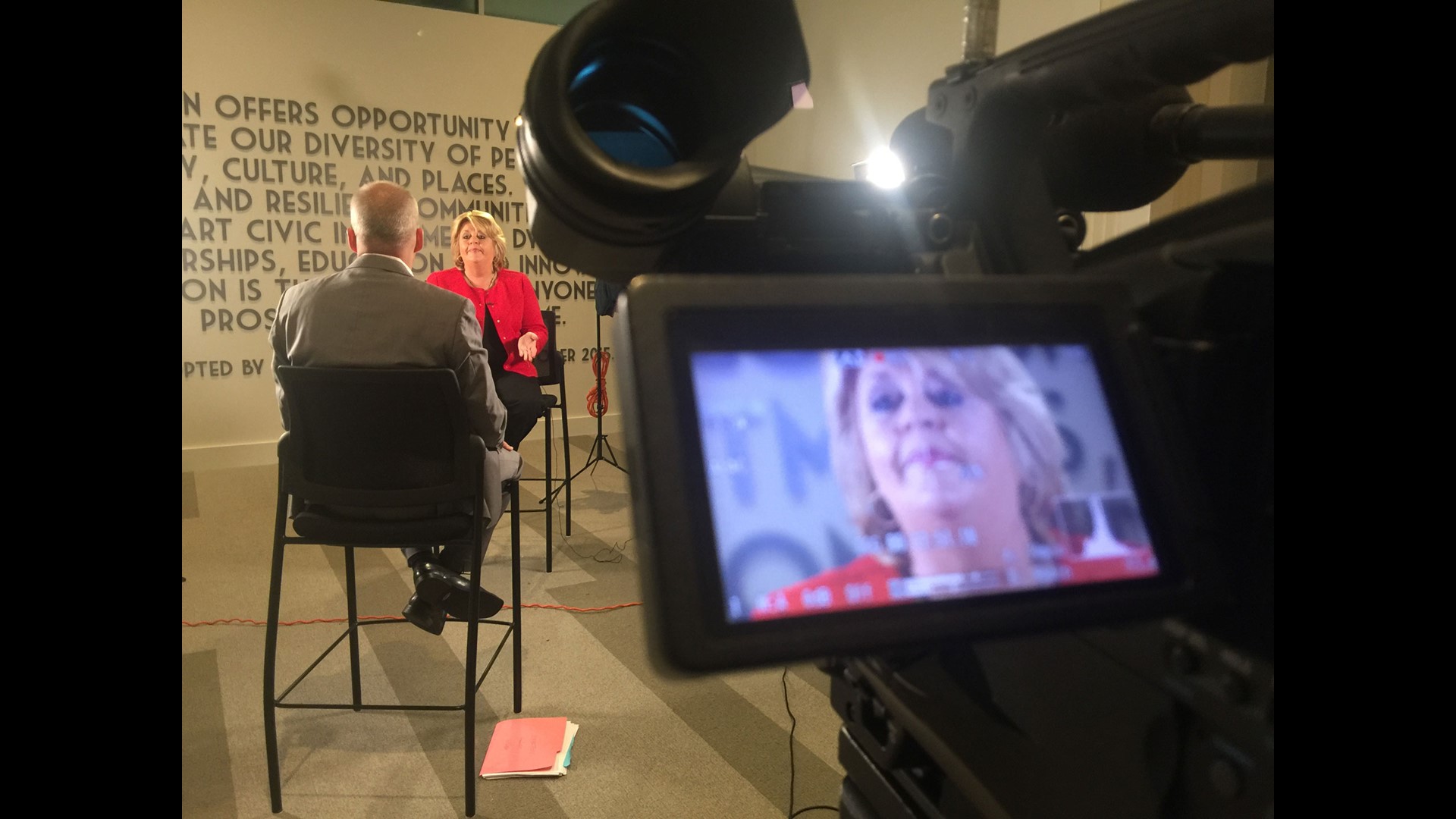

NOPD Deputy Superintendent Danny Murphy wants his department to be transparent, not use it as a saying. Murphy believes the best way for that to happen is to know when his officers are following policy.

“It’s a way to ensure that we’re using the cameras appropriately to allow them to fulfill their purpose of enhancing transparency and accountability,” Murphy said. “It takes a little bit of time to get to that utilization rate of a new technology.

“Now that we have sustained a very high rate of using the cameras, we’re confident that there is no incident that could take place and us not have the transparent documentation of what happened.”

New Orleans is the exception, not the norm. In fact, only five of the 62 departments sent KHOU documents responsive to random check-ups on who is hitting record and when.

Logging Issues

Like Oakland, the Fort Worth Police Department is guilty of losing body-camera evidence after an officer deleted video linked to a murder trial.

The footage was prematurely deleted due to improper logging and categorization. In Fort Worth, if a video receives no categorization, it’s retained for 180 days. Evidence labeled as criminal, which ranges from traffic stops to homicides, is kept for two years.

In 2015, Kenneth Ray Remble and Terry Ingram stood trial for murdering a North Texas man. An officer did not correctly categorize body-camera footage from the incident, rendering the evidence unavailable for trial. Both defendants were ultimately convicted. Fort Worth police said it’s the only known case with evidence prematurely deleted.

In Denver, accountability takes place every Monday.

Once a week, supervisors compile error reports for videos not properly logged into a cloud-based storage system. Like Fort Worth, Denver’s main problem with body-cam evidence was lack or improper identification and categorization of the video.

From January to August, all units equipped with body cameras in Denver amassed between five and 119 video logging errors. James Henning, Denver’s investigative support division commander, said the department phases in deployment of cameras at a rate of roughly 150 at a time. Most of the errors, he said, are due to growing pains with using the body cameras and then logging the video.

“We have a whole bunch of issues the first week,” Henning said. “Then with the audits we say, ‘OK, these officers have made mistakes and need to go back and correct them.’ After just a few weeks, we see a very limited number of mistakes. So it’s been a huge help.”

The reports build on the unrevised errors from previous weeks. Denver’s audits show that despite a large amount of errors in August, the majority of errors from previous months were corrected.

“Eventually, as we work our way through this, the audits will bring up the accountability to make sure the officers are using the tool,” Henning said.

However, most departments reviewed by KHOU don’t know what evidence they are losing since no routine audits are performed.

Rushed implementation

After the death of Freddie Gray and the riots in Baltimore, the city’s newspaper, The Baltimore Sun, investigated the Baltimore Police Department and lawsuits regarding police conduct.

The findings were immense. The Sun found that since 2011, the city of Baltimore used $5.7 million in taxpayer funds and another $5.8 million in legal fees to defend police brutality claims brought against Baltimore police. The city began to budget millions for future legal fees, according to The Sun.

Nearly three weeks after the newspaper’s investigation, a committee of citizens was appointed by the mayor to study the implementation of body-worn cameras. A year and a half later, Baltimore began rolling out a body-camera program at a cost of $11.6 million over the next five years.

While some police department have already implemented body cams, there are other agencies that have yet to purchase the tool for its officers, most notably the New York Police Department.

Of the 62 cities KHOU reviewed for their usage of body-worn cameras, 27 had no body-worn camera program in place. Several, such as Philadelphia, Boston, Sacramento, Kansas City and St. Louis, are testing how cameras work for their department.

“We’ve seen other agencies rush to get the cameras out and then have to pull them back because they couldn’t afford the storage costs or other issues,” Kansas City Chief of Police Darryl Forté said in a statement released by the department in September. “We don’t want that to happen in Kansas City. If we promise something to people, we want to be able to keep that promise.”

The Knoxville (Tenn.) Police Department said it is in no rush to purchase cameras and set policies. The department’s officers saw the public uproar when footage hasn’t been released. They saw the riots in Baltimore and the protests in Charlotte. They don’t want to welcome the same kind of problems to their city.

“We’ve looked at different cameras, but the problem we have are the concerns with privacy issues,” a department spokesman said. “Those need to be worked out prior to us implementing body-worn cameras. We’re not against it. Right now, there’s just major privacy concerns.”

With their body-camera purchases, departments nationwide added even more to its officers’ duties.

Take Fort Worth, where one administrator maintains 800 body cameras.

Fort Worth uses a camera that attaches to a shirt collar or eyeglass frame. The camera is at the end of a cord, which can fray, causing unforeseen malfunctions in the camera and recording capabilities. It also causes extra maintenance and repair work for that one administrator.

The Fort Worth police chief recently received approval for 400 more cameras, without an increased maintenance budget.

Lack of transparency

In order to be transparent, the video evidence behind police doors was supposed to be more easily accessible to the public. President Barack Obama demanded it. The Department of Justice funded it. But not all police departments followed suit.

In states like Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina, as well as the District of Columbia, laws were created to block the release of body-cam footage to most requesting parties.

The Norfolk (Va.) Police Department refused to release any body-worn camera footage to KHOU. It cited a Virginia law that states video doesn’t need to be released to non-residents. While NPD wasn’t obligated to release the footage, KHOU requested the department reconsider processing the request “in the interest of openness and transparency.”

The police department never responded.

In Greensboro, N.C., the public made seven requests for body-camera footage since February, all of which were denied. Officials cited a state law that prohibits the release of criminal investigation and government employee records.

North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory made his state even less transparent in July. McCrory signed House Bill 972, which states that body-camera videos are not public record.

Under the bill, the only way agencies must release video is if people who are shown or heard in the footage, or personal representatives of those individuals, request the video.

Two months later, on Sept. 20, Charlotte-Mecklenburg police fatally shot Keith Lamont Scott, the 703 person shot by police this year, according to The Washington Post.

As helicopters flew overhead, protestors rioted amid police officers armored in SWAT gear. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Chief Kerr Putney held onto the wooden podium with both hands. He carefully chose his words as he described a video that still had not been released to the public.

A reporter questioned Putney’s mixed messages.

“On the one hand you’re saying we should get full transparency,” the reporter said. “On the other hand, you’re saying you’re not going to release the video. How can you square those two things?

“Obviously the idea of full transparency is release the video so we can all see it.”

Putney adjusted the mic.

“Sure. I appreciate your passion,” Putney said. “But I never said full transparency. I said transparency. And transparency is in the eye of the beholder.”