Thousands of Texas criminals are out on the street, and the agency in charge of supervising them has no idea where they are, a KHOU 11 Investigation has found.

They are parolees serving the remainder of the prison sentences in communities across Texas, but have failed to report their parole officer as required.

According to the Parole Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, there are 7,273 of these fugitives statewide and 1,483 in the Greater Houston area.

Nearly 350 around Houston are flagged as “violent offenders” with convictions including aggravated assault, robbery, sexual assault and murder. With their whereabouts unknown, the victims of their crimes are often left living in fear.

Willa Burns is one of them. When she started dating Adrian Lindsey, she said he was a “charmer,” but their relationship turned from romantic to violent when he began using drugs.

“Once he started using PCP, I was his punching bag,” Burns said. “(He was) very abusive."

Court records show abuse culminated when Lindsey kidnapped his then-girlfriend Burns in November 2008, dragging her into an abandoned home and began hitting her over the head with a closet rod.

Lindsey was sent to prison for the crime, and it wasn’t his first time. He had previous convictions for aggravated robbery, assault and drugs.

Records also showed he was hospitalized for mental issues and told doctors he had attempted suicide several times and was “hearing voices.”

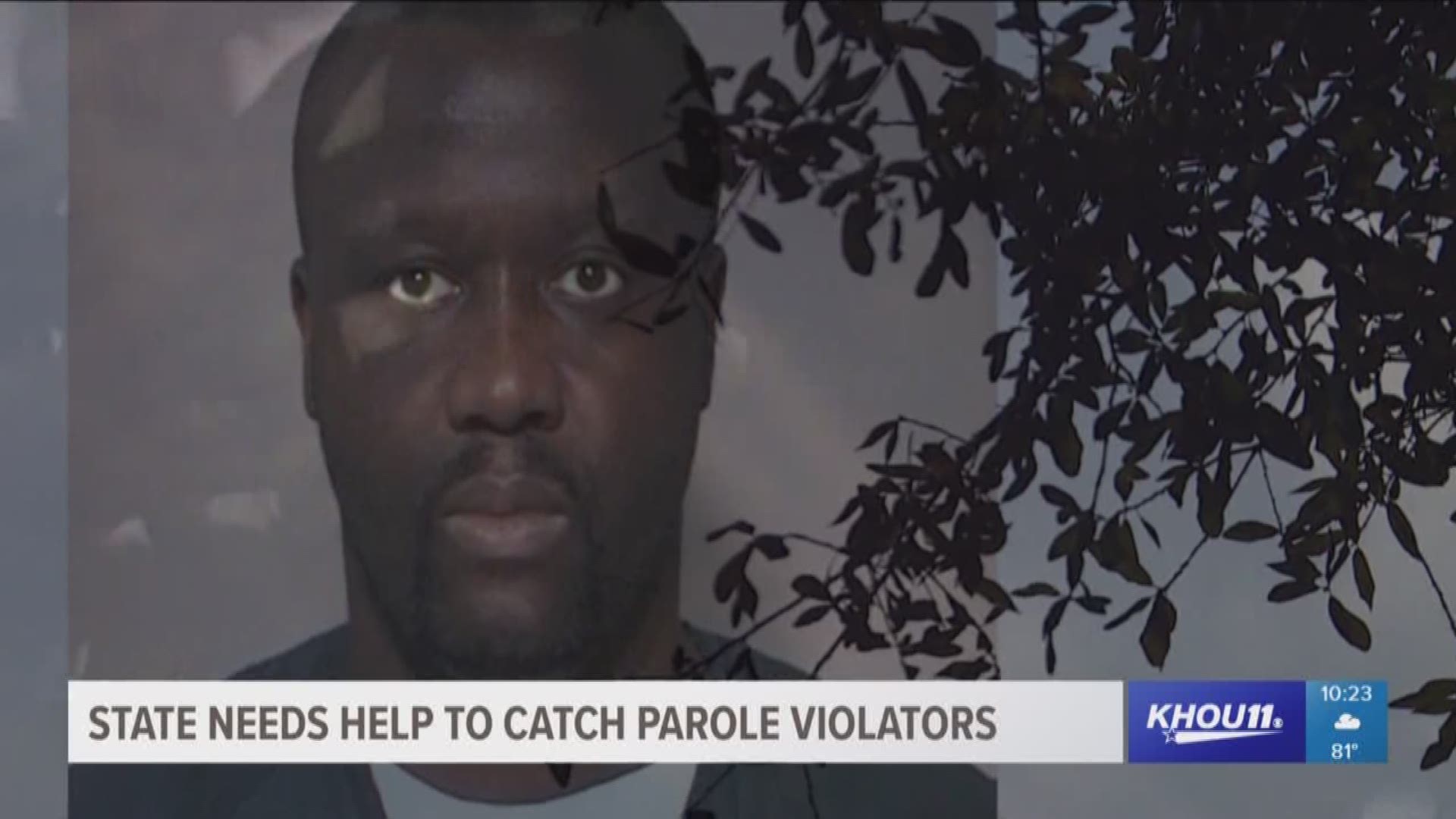

Lindsey was sentenced to 25 years in prison for that 2008 crime but was released on parole in May 2015. About a year later, he stopped reporting to his parole officer.

The State of Texas has not been able to locate the convict ever since.

“Get him off the street, please get him off the street,” Burns said. “He can do it to somebody else. If he did it to me he can do it to somebody else,” she said.

Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo said cases like Burns amount to re-victimizing the victim.

“The bottom line for me, it’s a problem,” Acevedo said.

He said there must be consequences for offenders who don’t follow the terms of their parole and go off the grid.

“I think all of us in law enforcement need to do a better job of finding them and bringing them into custody.” Acevedo said.

But the hands of parole officers are tied to an extent, given that they don’t have police powers.

“The parole staff, the parole officers do not have the authority to arrest individuals,” said Pamela Thielke, director of the Parole Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Thielke said her agency can only issue warrants for parole violations. It must rely on law enforcement across Texas to try and serve those warrants.

Many times that occurs when a fugitive is stopped for a traffic violation. But Theilke said regular “roundups” of parole violators are a matter of local resources and manpower that are out of the state’s control.

“Do I wish that was a number one priority? I mean I’d like to say yes, but I also have a healthy respect for other things that may be determined a greater priority at that time,” Thielke said.

For victims like Willa Burns, it means constantly looking over her shoulder in fear.

“He already knows where I’m at,” Burns said, choking back tears.

TDCJ also enlists the public’s help in locating parole fugitives. The agency has a Facebook post called Wanted Wednesday, that features a new fugitive parole violator every week.

TDCJ also has a tip line people can call if they know the location of that wanted parolee. That number is (866) 680-6667 and is open 24 hours, seven days a week.