A maze of metal cages covered the property, the volume accented by a chorus of crows. Inside each pen, brightly-colored roosters loomed on perches or strutted to the front of their enclosures to protect their territory.

Along the back-fence line, a woman pointed to a half dozen perfectly groomed, posturing gamecocks, and raised her voice above the squawking birds.

“They’re going to fight them,” she said. “They’re on a diet and they get vaccines and stuff like that.”

This was not a farm in a rural area outside of Harris County. This was the backyard of a modest wooden home just a few blocks away from a major intersection in northeast Houston.

“It looks to be a very well-funded, well-oiled cockfighting breeding operation machine,” said Katie Jarl after watching a KHOU undercover video inside the operation. Jarl is the Texas senior state director for the Humane Society of the United States.

The state toughened up its cockfighting laws seven years ago, but KHOU 11 Investigates found few busts of the blood sport in Harris County, despite the ease of finding apparent cockfighting operations.

‘A blood sport’

Cockfighting pits roosters against each other. The birds’ legs are fitted with sharp razor blades, so they can fight to the death while gamblers place bets.

Fights can last anywhere from a minute to half an hour, until one—or both—of the roosters dies, Jarl said.

“They call cockfighting a blood sport for a reason: it is gory,” Jarl said. “Often times the weapons they fasten to the rooster’s legs will slash open another bird.”

That’s why it’s now a crime to simply possess those slashing blades. Seven years ago, it was only illegal to participate in a cockfight in Texas, but actual participation often was hard to prove.

So, Texas beefed up its cockfighting laws in 2011, making it illegal to possess slashers, gaffs or other fighting implements; attend a cockfight; or to raise, buy or sell fighting roosters.

“There is no need for a civilized society to put two animals in a ring and wage money on who dies first,” Jarl said.

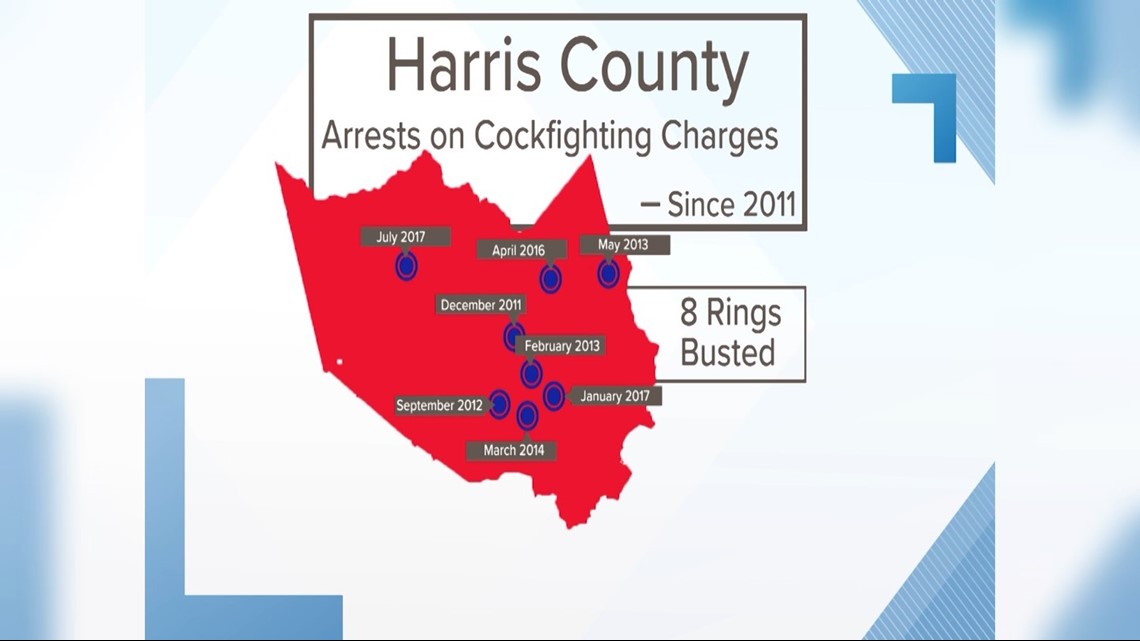

But when we pored through court records, we discovered that since the new laws were passed seven years ago, police have only busted eight cockfighting rings in Harris County.

Hidden in the open

Sgt. Jason Alderete, the head of the Houston Police Department Animal Cruelty Squad, blamed the few arrests on the clandestine nature of cockfighting.

“This is an underground sport,” Alderete said. “It’s usually done in a rural environment or a location that’s difficult for police officers to see from the street.”

But it wasn’t difficult for our undercover cameras to find signs of cockfighting.

Online, there were several Craigslist ads, YouTube posts and at least four Houston-area Facebook groups with hundreds of people buying and selling roosters and cockfighting accessories.

It only took a few phone calls and a short drive to that modest wooden home to see what was for sale.

Surrounded by a wrought-iron fence, the house looked unassuming among the small brick and wood homes that dotted the working-class neighborhood. A Doberman pinscher puppy menaced beside the carport, but it wasn’t his barks that sounded out of place, it was the constant rooster crows.

Through the carport and into the backyard, two women weaved through the lines of cages, showing off roosters. Most were without combs or wattles, a common practice called “dubbing” that keeps roosters fast by removing body parts that would be easy for opponents to grab hold.

The women explained that they were selling the roosters on their husbands’ behalf, who weren’t there at the time, but who often sold roosters online.

“You know, the community is big,” one of the women said.

After pointing out the six roosters that their husbands were raising to fight themselves, one of the women made her way to the other side of the yard, walking past the incubator holding fluffy chicks and dozens of cages covered by small tarps.

She pointed out a rooster with shining red-and-green feathers known as “Calibre Cinquenta,” or “50 Caliber,” her husband’s favorite.

“He’s killed about four roosters,” she said.

Manpower an issue

The apparent cockfighting breeding ground was not exactly underground, but police said limited resources make it difficult for them to conduct proactive undercover investigations.

“We only have three officers to do that with,” Alderete said. “We’re not able to do that at this time, unless we get more people.”

Manpower also is an issue at BARC, the city of Houston’s Bureau of Animal Regulation and Control. Jarrad Mears, BARC’s animal enforcement division manager, pulled up a dispatch computer screen and pointed to a long queue of calls.

“On any given day, the city usually has seven to 10 people, seven days a week, answering hundreds of calls a day,” he said.

The agency received more than 3,500 complaints about chickens since 2014, but were unable to respond to 75 percent of them.

Mears said he thought most of those calls had to do with noise complaints or foul odors.

“You have to understand that three quarters of those calls aren’t cockfighting calls,” he said.

But when questioned, Mears backed off that statement and said he didn’t know for certain, because animal control officers never went out to those calls.

“There’s no way that BARC can answer every single call that we receive with the current staffing that we have,” Mears said.

However, Mears said his agency does forward callers to the Houston Police Department’s non-emergency line.

“What I want to hit home at is, HPD will receive that call, so it’s not entirely going ignored,” Mears said. “It just means that BARC doesn’t have the manpower to investigate it at that moment.”

Once calls are transferred, a police dispatcher determines how important the call is and a patrol officer will respond accordingly, Alderete said.

“On a busy night, which is when these fights are usually occurring … it might take a while to respond to that call,” he said.

And when police get there, finding a cockfight in progress is near impossible, Alderete said.

“Usually, if there’s a fight in progress, from my understanding, there’s going to be people running everywhere, and the actors are gone, the only thing left is going to be chickens and beer bottles,” Alderete said.

That was the case during a bust in 2012. HPD arrived at a bloody scene to find a trashcan full of dead roosters and several injured birds near a large wooden ring similar in size to a boxing ring.

Most of the suspects ran, but HPD found one man with roosters in his vehicle and arrested him for possession of a fighting rooster. He served four days in jail and paid a $4,000 fine.

RAW VIDEO: HPD busts cockfighting ring

That short sentence is typical. Like the 2012 case, another large wooden ring was discovered in 2014. Police videoed the ring, capturing images of feathers scattered around and a scoreboard on a dry-erase board.

Two men were charged with felony cockfighting in that case, but both charges were bumped down to misdemeanors. One man was sentenced to 60 days in jail, the other 120 days, the longest cockfighting sentence in Harris County since the new law took effect.

A handful of other spectators also were arrested and ordered to pay a $300 fine.

“I would absolutely hope to see more criminal cockfighting cases in the future. We have a tough law on the books and we’d like to see it used,” said Jarl of the Humane Society.

In one of the most recent Harris County cockfighting cases, 140 roosters and hens were seized, and the owner was arrested for misdemeanor possession of a cockfighting slasher in January 2017. He served 40 days in jail.

The arrest came after five complaints to BARC and multiple visits to the property over four months.

Changes in the works

The city of Houston is now changing the way it is doing business after KHOU 11 Investigates questioned why most cockfighting complaints are given a low priority.

A review of cockfighting calls to BARC revealed three-fourths were marked priority four, the second lowest on a scale of one to five.

“If they’re put in as a priority four or five, the officer is not going to look at those calls,” Mears said. “The officer, due to the severity of other situations, may not see that call, and it may get closed out.”

Mears conceded that calls may be misprioritized and said BARC will now categorize cockfighting calls as priority two, making it much more likely they’ll get a response.

In 2017, BARC responded to 96 percent of its priority two calls, according to BARC statistics.

In addition, BARC is now part of the Harris County Animal Cruelty Task Force, and people are encouraged to report animal cruelty to 927Paws.org or by calling 832-927-PAWS (7297).

“We’ll definitely take it serious, very serious,” Mears said. “It’s a very sad situation when you’re making money off of animal suffering and dying.”

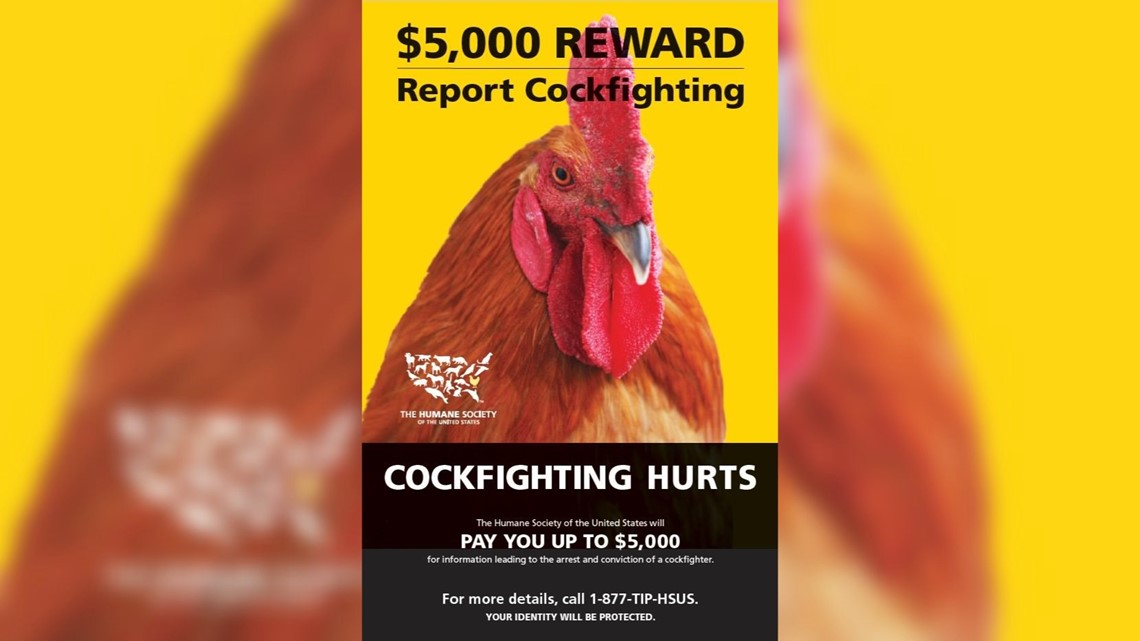

Along with reporting animal cruelty to the task force, cruelty can also be reported to the U.S. Humane Society 1-877-TIP-HSUS. They offer a $5,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of a cockfighter.

Dealing roosters

Back in the backyard in Northeast Houston, it was business as usual. One of the women explains why the beautiful red-and-green rooster, “Calibre Cinquenta,” was not for sale.

“(My husband) already retired him because he hurt a leg, and he just has him now for babies,” she said.

That offspring and at least 50 other young roosters were all for sale and all cost hundreds of dollars, depending on their age, breed and experience.

“They’re selling the rest of these for about $200 and these are about $500 or $600,” said a second woman selling the roosters. “And they’re mean.”

The seller paused when asked the best price she could give.

“I’ll make you a deal,” she said. “If you take at least three, I can do at least $170 each. That’s the lowest we can do.”

Photos: Cockfighting rings busted across Harris County

Additional reporting by Danny Hermosillo.

Follow Tina Macias, Jeremy Rogalski and Danny Hermosillo on Twitter.