This story is part of KHOU 11 Investigates' series “Unforgivable.” Parts may contain graphic descriptions of sexual assault. If you or a loved one have experienced sexual abuse, get help through the free and confidential National Sexual Assault Hotline (1-800-656-HOPE).

It’s been 15 years since James Harmon lost his brother.

It was March 2003 and James received the phone call while playing with his newly adopted kitten. James always worried about John, who had struggled with post-traumatic stress, depression and drug addiction for years. Now, at 30, he was dead.

“He had both medications in his system for trying to counter drug abuse and anxiety, as well as cocaine and other drugs,” James said. “What that meant was he was fighting. He was fighting that trauma and everything that happened to him.”

John’s cause of death will forever be listed as an accidental drug overdose, but his family believes there was another cause. His addiction was rooted in sexual abuse that John suffered for years at the hands of two men — a family friend and later a priest who was supposed to counsel him.

“It was the fact that he was abused and then abused by a member of the church that should’ve been helping him. That’s exactly what caused his death,” James said. “There is no doubt in my mind that the church is responsible.”

‘All-American family’

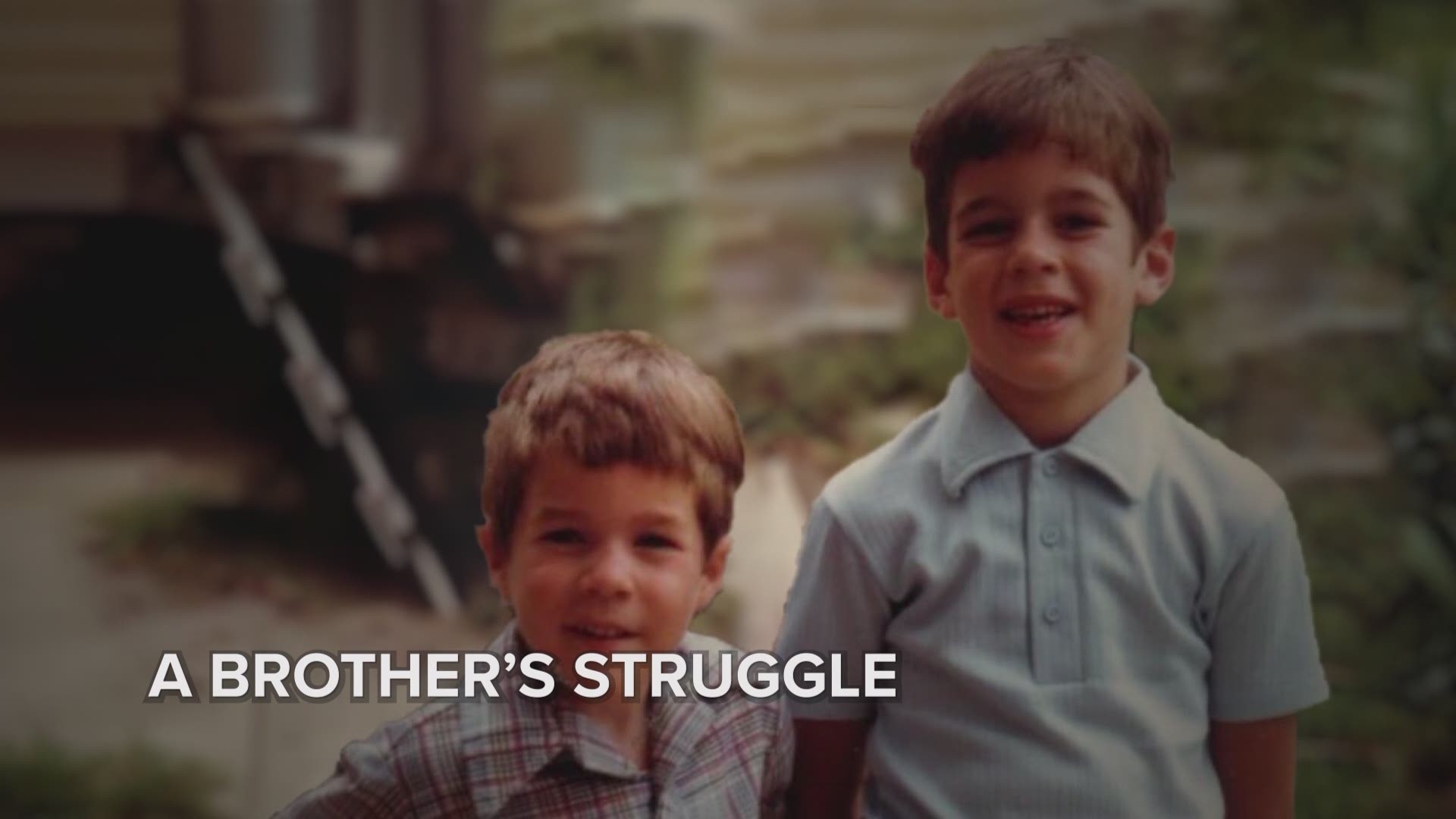

James and John spent their childhood outdoors in the 1970s and 80s. Their days were filled with playing with the family dog, shooting BB guns and taking turns on water slides at Lake Texoma. Their family was devoutly Catholic.

“(Church) was at least once a week, Sunday Mass, and a lot of times, of course,” Holy Days of Obligation,” James said, who described his childhood as growing up in an “All-American family.”

John served as an altar boy at his family’s church.

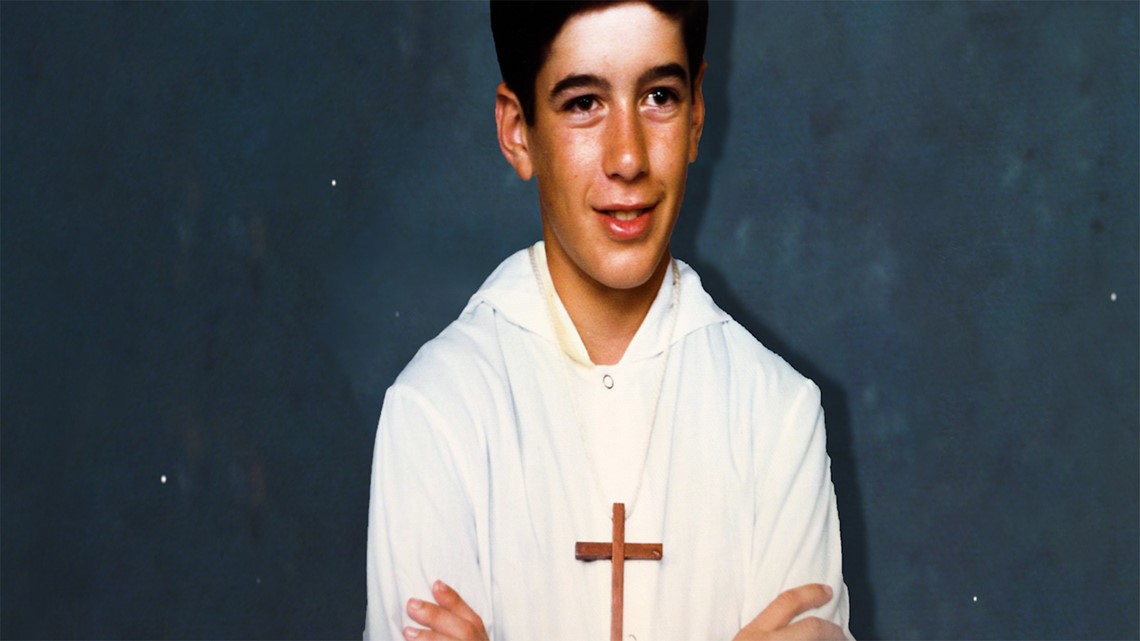

But that happy childhood and innocence unraveled when John was 13. His family noticed a change in him and learned John was being molested by a family friend — a man who was later convicted of indecency with a child. To help John deal with the trauma, a police officer recommended he see Rev. Dennis Peterson, who worked with troubled teens.

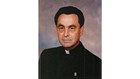

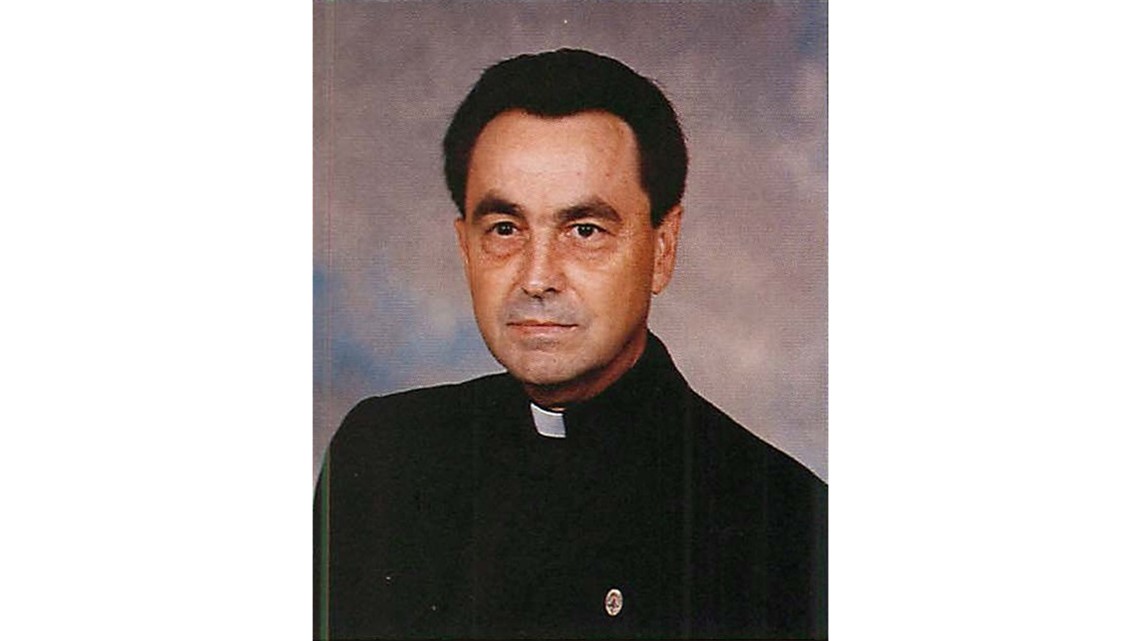

Peterson was the director of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston’s Special Youth Services and a chaplain at the Harris County Juvenile Detention Home.

“We looked at the church as a trusted resource, so to have a priest that’s also able to double as a counselor, that would have been a godsend,” James said.

Instead, Peterson told John that what the family friend did to him wasn’t wrong, John said in court records. Peterson fed John drugs and alcohol and then would “pull down his pants” and “do his business,” James said.

“The abuse that he had already experienced was just confirmed, and it just twisted his mind,” James said. “He was conflicted until the day he died.”

Peterson and the archdiocese both denied the allegations in court filings.

A decade of damage

The abuse lasted 10 years — from 1987 to 1997, according to court records —during which time John fell deeper into his addiction, fueled by drugs supplied by Peterson, John said in an affidavit. John ran away at times and ended up on the streets, but he often came back home and went to Peterson for confession, James said.

“(Father) Dennis continued with the abuse rather than trying to help him,” James said. “He told him that you can’t go to your family and that we can resolve everything by going to confession and going to God.”

James always felt Peterson was a little off. He had an interest in kid’s video games, and once James helped him install a game on his computer. At the time, James thought he was helping his brother. He said he later realized Peterson used video games to groom children.

“That’s what has hurt me so deeply over these years, just knowing that the person that is supposed to be in the role of the shepherd is the person that literally is the wolf and doing so much damage to my family,” James said. “I mean, to this day, it’s a tremendous impact to us all.”

‘Do the right thing’

John sued Peterson and the archdiocese in 1999. Three other accusers — two brothers and their sister — joined the lawsuit, too, saying they were abused by Peterson in the 1970s at St. Bernadette Catholic Church.

Peterson denied the allegations and the archdiocese ultimately settled out of court for an undisclosed amount of money. A grand jury also considered charging Peterson with sexually assaulting John when he was an adult but declined to indict him in 1999.

Peterson was sued again in 2005 by an adult who said, as a seventh grader in 1983, he met Peterson at a juvenile detention center and was then raped at Peterson’s living quarters at St. Michael Catholic Church for three days. The diocese and Peterson denied the allegations, but also settled out of court, according to court records.

Peterson died in 2007.

“(He) has an obituary that says all these wonderful things about him,” James said. “He died of his own medical complications … never having served time. Never being addressed.”

The archdiocese said in a statement it did address the accusations by removing Peterson from ministry and later defrocking him. However, Peterson was still allowed to live at a church and later a priest retirement home until his death, according to the archdiocese.

Peterson was on medical leave living at St. Theresa Church when the first suit and criminal charges were filed and remained there for years under “supervised suspension,” the archdiocese said in a statement.

The diocese addressed the living situation in 2002 when the parishioners were also told Peterson suffered from a brain tumor.

“They were told that he was in residence at St. Theresa’s but that he had no parish or school responsibilities and that the Diocese did not believe he was a risk to minors or anyone else,” an archdiocesan statement reads.

Then, at the recommendation of a Review Board in December 2003, the process of laicizing or “defrocking” Peterson began and was approved by the Vatican in 2005.

“When laicized, Dennis Peterson was in poor health and the archdiocese permitted him to live in a facility for retired and infirm priests,” an archdiocesan spokesperson said in a follow-up email.

It’s unknown whether the archdiocese will address Peterson’s accusations publicly by including him on the list of “credibly accused” priests that the it plans to release soon.

“It would be a good start,” he said. “If Dennis Peterson is on that list that would restore some of my faith in the church that they’re actually making change and they’re starting to do the right thing.”

James grapples with his own faith these days, unsure whether to call himself a Catholic.

“I still firmly believe in God, but as far as Catholicism, I feel the church has not stood by me and has not stood by my family,” he said. “I feel like the church was more interested in saving face and protecting their own than actually taking care of the problem and caring about the families.”

James still thinks about his brother often. Christmas is especially difficult. So, too, are the days surrounding John’s birthday and every March around the time John died. He remembers the time it looked as if John was putting his life together, back when he got married and later had a child.

But John’s addiction proved too strong.

“I feel like he was using the drugs to burn those thoughts and memories out of his mind,” James said. “There is no doubt in my mind that my brother would be alive today had he received actual help from Father Dennis Peterson.”