Mars may have claimed another victim.

Europe’s Schiaparelli lander, scheduled to settle into the Martian dust at 10:48 am ET Wednesday, fell silent only a minute or so before its scheduled landing time. It’s too early to declare game over, but officials with the European Space Agency acknowledged the failure of both an Earth-based telescope and a Mars-orbiting spacecraft to detect signals from Schiaparelli is worrisome.

“It’s clear that these are not good signs,” said Paolo Ferri, the space agency’s head of mission operations. “But we will need more information.”

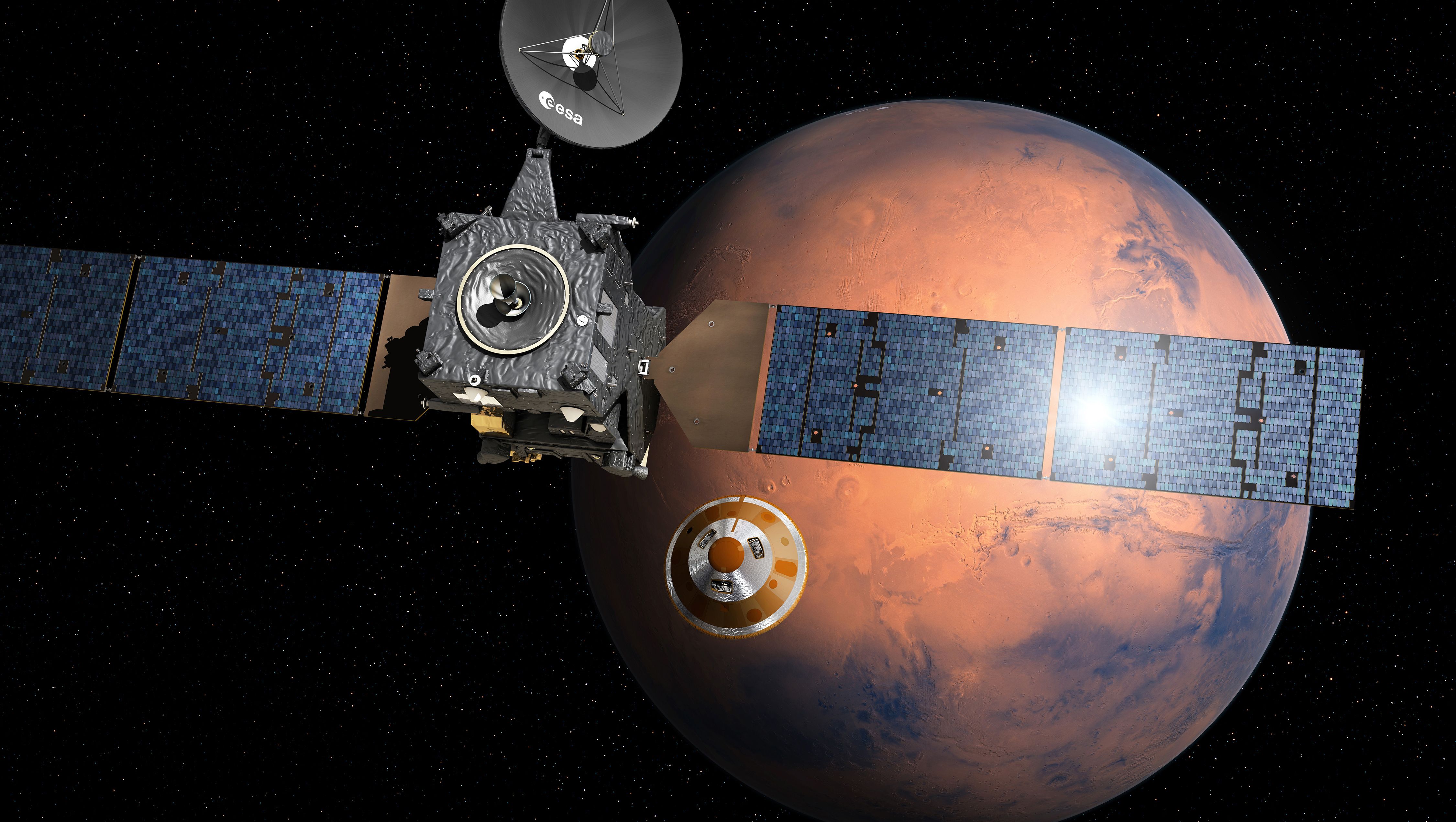

Ferri said engineers will work around the clock to analyze data from Europe’s Trace Gas Orbiter, which swung into orbit around Mars on Wednesday and may hold a cache of information transmitted from Schiaparelli, a stationary research base aimed primarily at testing landing technologies. Officials hope NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter will have some intelligence to offer, too.

Unless engineers establish the craft is alive and well, Schiaparelli will join a long list of landers that fell victim to Mars’ dangerous charms. Over the past three decades, roughly half of all Mars missions, which includes both landers and orbiters, have failed. Vehicles that dared to aim for Martian soil have burned up in the atmosphere, smashed into the surface or missed the planet entirely. The list of spacecraft that arrived safely on the Martian surface numbers only seven.

For much of Wednesday, it looked like Schiaparelli would make it eight. As the lander descended toward the Red Planet, a giant telescope in India picked up signals suggesting Schiaparelli abruptly reduced its speed, an expected response to the opening of its parachute. Later signals established the parachute ripped away from the craft as intended, revealing nine thrusters that were supposed to slow the craft even further.

But then the Indian telescope lost the signal, as did Europe’s Mars Express spacecraft.

Not all was lost, though. Mission personnel were jubilant over the Trace Gas Orbiter’s successful arrival into Martian orbit. The orbiter, which launched with Schiaparelli in tow in March, will sniff out gases such as methane that may have been generated by living things.

The orbiter also offers scientists hope for squeezing information out of Schiaparelli if it is not recovered. The lander was supposed to collect unprecedented data on the Martian atmosphere during its descent and beam it to its sidekick in orbit, and there’s a “very good chance” it did just that, said Colin Wilson of the University of Oxford, a scientist involved with Schiaparelli.

On the other hand, the Schiaparelli instrument that Wilson personally oversaw wasn’t scheduled to collect data until the lander was safely on the Martian surface, a now-iffy scenario. This would not be Wilson’s first disappointment: he planned to collect data from the same kind of instrument on Britain’s Beagle 2 Mars lander, which landed on Mars in 2003 but failed to make contact with Earth.

“It’s like getting slapped twice,” Wilson said. “But we have an orbiter that's gone into orbit around Mars … and it’s going to last for years,” whereas the lander was intended to survive only a few days.

Schiaparelli was designed to test technologies for a much larger roving laboratory scheduled for launch in 2020. Its disappearance puts the timing and design of that mission in doubt.

“Mars for many reasons is a very difficult target,” said Olivier Witasse of the European Space Agency. “Success or failure, we have to continue and learn from that.”