Reginald Lewis Gordon hid every day. At home, away from his father’s abuse. At school, in the back of the classroom.

At night, Gordon watched his father, a steelworker and truck driver, kick his legs on the couch and chug alcohol all evening. In the morning, when his uber-religious mom woke her six children up for school, Gordon saw his mom’s black eyes and bruises.

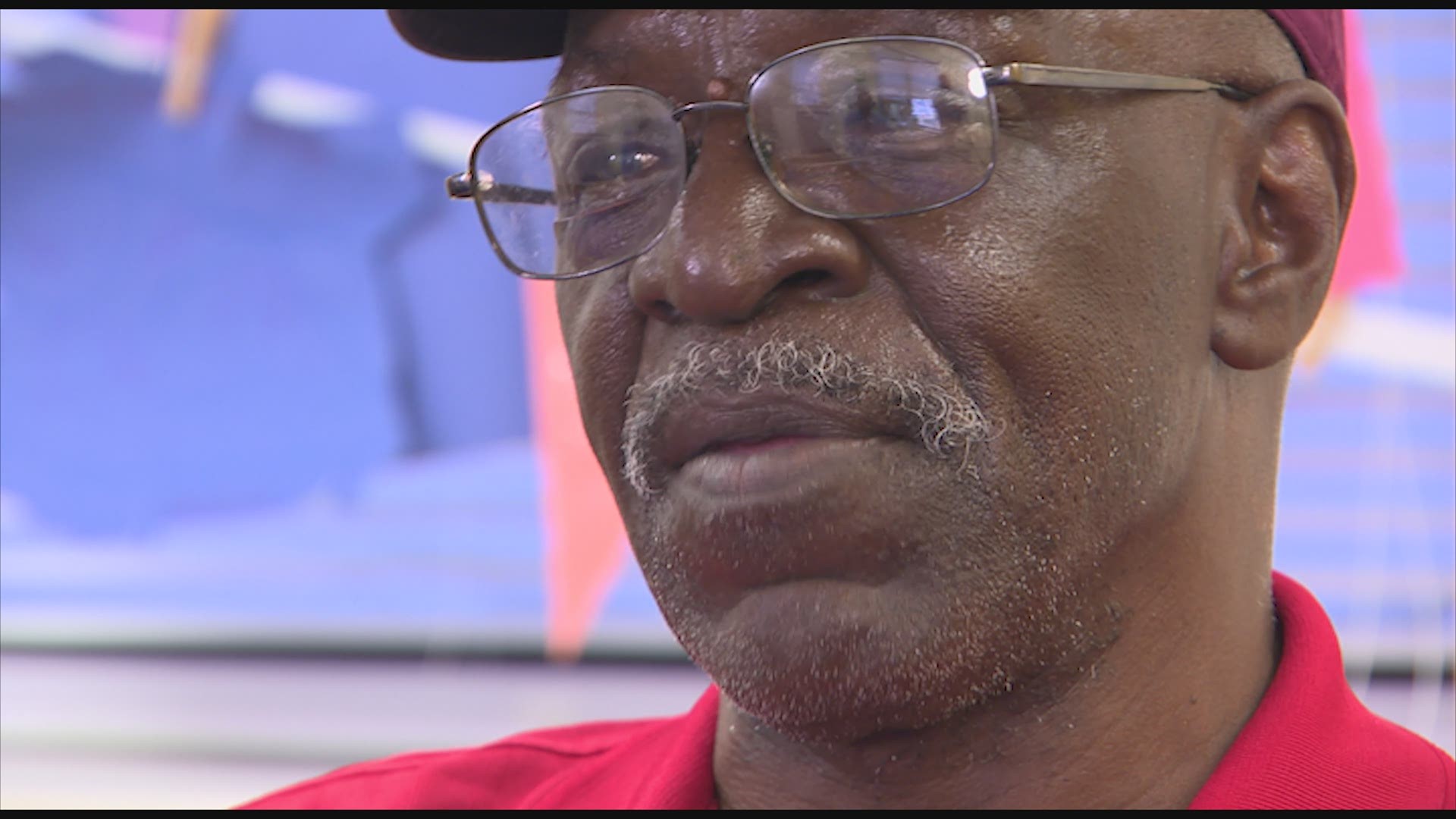

“She would tell us, ‘Don’t worry about it. Your daddy, he just had too much to drink,’” Gordon, now 58, said. “I would look at my mother like, ‘Why would you let this man hit you like this here?’”

His mother told him not to tell anyone about his father’s abuse, which angered him—anger that he carried to school.

That’s why the quiet, skinny teenager sat in the back row of his seventh-grade classroom, hoping teachers at Richard Dowling Middle School ignored him. He feared embarrassment: What if other kids heard him struggle to read simple sentences? He learned through the years that if he showed up on time, most teachers ignored him.

“If you showed up every day, they passed you to the next grade because they didn’t care if you were dumb or not,” Gordon said. “So, I was a dumbass in the seventh grade.”

At 14, all Gordon wanted was support—from his parents, his teachers, anyone—but when he didn’t find it at home or school, he turned to a local gang. He started skipping class with people who seemed to care and understand his pain. His gang promised him the loyalty, respect, power and security he craved.

“When we’re not accepted by people that’s supposed to love us and look at us and look through us, we find other people to make promises and good promises to us,” Gordon said.

They cut class to smoke and drink, of all things, wine at a local food store. They robbed people and stole from stores on South Post Oak Road to make money. Then the Houston Police Department dragged Gordon and two others for questioning.

They were suspects in four violent robberies.

Houston has 353 gangs and nearly 20,000 documented gang members. That’s four times the number of uniformed police officers. KHOU 11 Investigates analyzed six years’ worth of reports and found that gang crime happens in almost every part of the city. The hottest spots for such crimes are in southeast Houston, according to HPD data, where four neighborhoods rank among the police department's busiest for gang activity.

Troy Finner is in charge of homeland security for the Houston Police Department. He’s a 28-year veteran who also grew up in Hiram Clarke, the same southwest neighborhood that Gordon called home. Finner had a much different upbringing: no abuse at home; his parents sent him to school clothed in support; and in third grade he found perhaps his biggest supporter, his teacher Evelyn Spencer, who he grew to consider a second mom.

Spencer’s encouragement helped Finner succeed through high school, where he played football for James Madison and dreamed of going into business. Finner never considered a career in law enforcement. He’d seen officers mistreating his friends and family, whether through their own faults or not.

“I didn’t really have a positive relationship,” he said. “I didn’t have a bad relationship with them, either, because it wasn’t a whole lot of personal interaction.”

But Finner found a love for law enforcement while taking a serial murder class at Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, nearly 100 miles north of his southwest Houston home. The challenge and reward of bringing justice to families called to him.

Finner graduated at the top of his class, the first college graduate in his family. Instead of chasing coveted work with the FBI or other federal agencies, Finner returned home to Houston to help the Houston Police Department.

In his nearly three decades with HPD, Finner has seen all kinds of crimes. But It was the death of an 8-year-old boy shot and killed in a gang-related crime on March 1 that broke his heart.

Tristan Hutchins was playing in a parked car with his 5-year-old sister and 11-year-old brother on Scott Street near Wheeler in the Third Ward when, without warning, a gunman fired shots into the back seat.

Finner was celebrating his 51st birthday the night of the shooting. Finner is a father to his own 8-year-old and uncle to two others killed by gang violence in southeast Houston.

He arrived at the crime scene in tears.

“I made a promise to that family that we are not going to stop until we get each and every person that’s responsible for his death,” Finner said. “That day, once I left the scene, I had this picture in my mind of that young man, his brother and his sister in that car playing what kids do at that age just having a good time, never knowing that danger was on them.

“This is what motivates me and this is what motivates our entire team.”

Hutchins died weeks later.

Police believe the alleged killer is 17 years old.

Detectives will only say the motive is gang related.

Houston’s average gang member is between 13 and 30 years old, according to the Houston Police Department. While many are part of traditional groups that use colors and tattoos to identify themselves, others do not, which makes their gangs hard to identify and investigate.

In 2012, a $1.75 million grant for the Texas governor’s office created the Texas Anti-Gang Center to target violent gangs and transnational criminal organizations. They have an undisclosed headquarters for investigators, analysts and prosecutors from various local, state and federal agencies. Most of its investigations are into active long-term conspiracy cases on state, regional, national and international levels.

When it comes to investigating cases in the Southlawn and Sunnyside neighborhoods in southeast Houston, less than half of those cases—39 percent—have been solved since 2013. The challenge, Finner sees, is not enough people trust police or provide tips.

In the Third Ward, not far from where Hutchins was shot, an 81-year-old homeowner said she sees two or three people getting shot every week, including her son who was murdered.

“Jesus is going to have to step in and do something,” the woman said, asking for anonymity because she fears retaliation. “I just don’t see (police) solving the problem because these people don’t care about jail anymore.”

Though Reginald Gordon put on a tough guy persona during his police interrogation after he was arrested for robbery, deep down he feared going to jail. Detectives demanded Gordon confess to using guns to rob four people. Even after 11 hours in an interview room, Gordon told detectives he knew nothing—over and over and over again. Gordon believed his partners did the same.

He later learned in court they gave him up. For all the talk of loyalty, respect, power and security, Gordon was sentenced to 50 years in prison. He choked when the judge read the sentence. Then, as deputies shackled and led him away, Gordon saw his mom and pregnant girlfriend cry in the courtroom.

That anger he carried as a teen turned to rage.

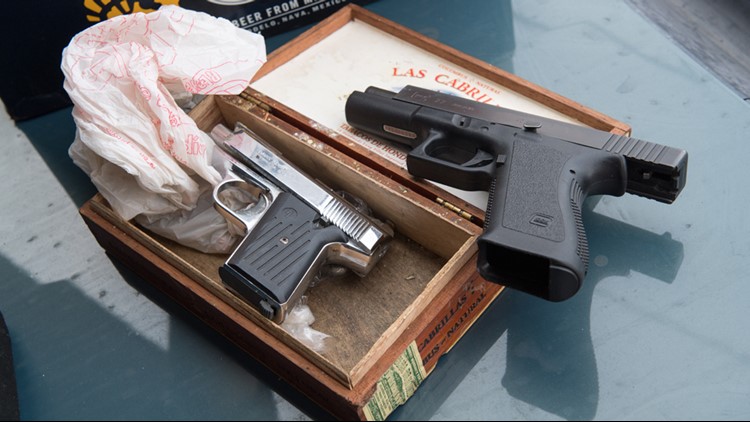

Photos: Operation Triple Beam

In prison, he fought rivals. He stabbed a man and was sent to solitary confinement—a dark place where he was left with his thoughts. But there he discovered his goals. First, he wanted to get to a more relaxed prison unit. The warden offered him a path if he avoided trouble and agreed to study for his GED. He did both. Deep down, education is what Gordon craved. He later found the attention and motivation he desired in the Ferguson Unit in Livingston.

“Support gave me a sense of looking at myself a different way,” Gordon said. “I had to look at myself because somebody else loved me more than I loved myself. Support kept me moving.”

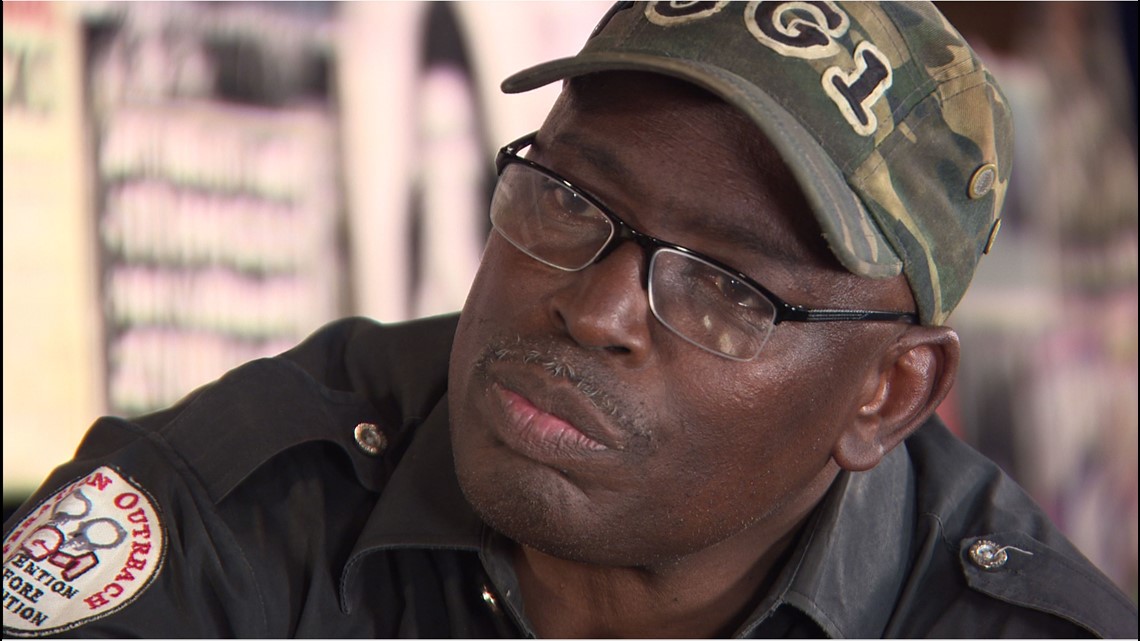

Once released, he started Operation Rescue, also known as OG1. His organization works to rehabilitate young people convicted of gang-related crimes, first-time offenders currently locked up, teens getting recruited by gangs and those dealing with anger-management issues.

His group recently spoke to students at James Madison High School, Finner’s alma mater. With his voice straining, Gordon begged the teens to listen.

“I’m sitting here telling you because somebody in this room will end up in jail,” Gordon said. “ You’re thinking, ‘It won’t happen to me.’ Hell, I wasn’t supposed to go to jail, either.”

Like Gordon, so many local organizations are motivated to help all children affected by gangs have options—especially those troubled in southeast Houston. These organizations attack Houston’s gang problem through education, health care and outreach intervention.

Many work on their own, all wanting to make a bigger impact but admitting to needing help, more attention and the need for people to step up.

Photos: Operation Triple Beam

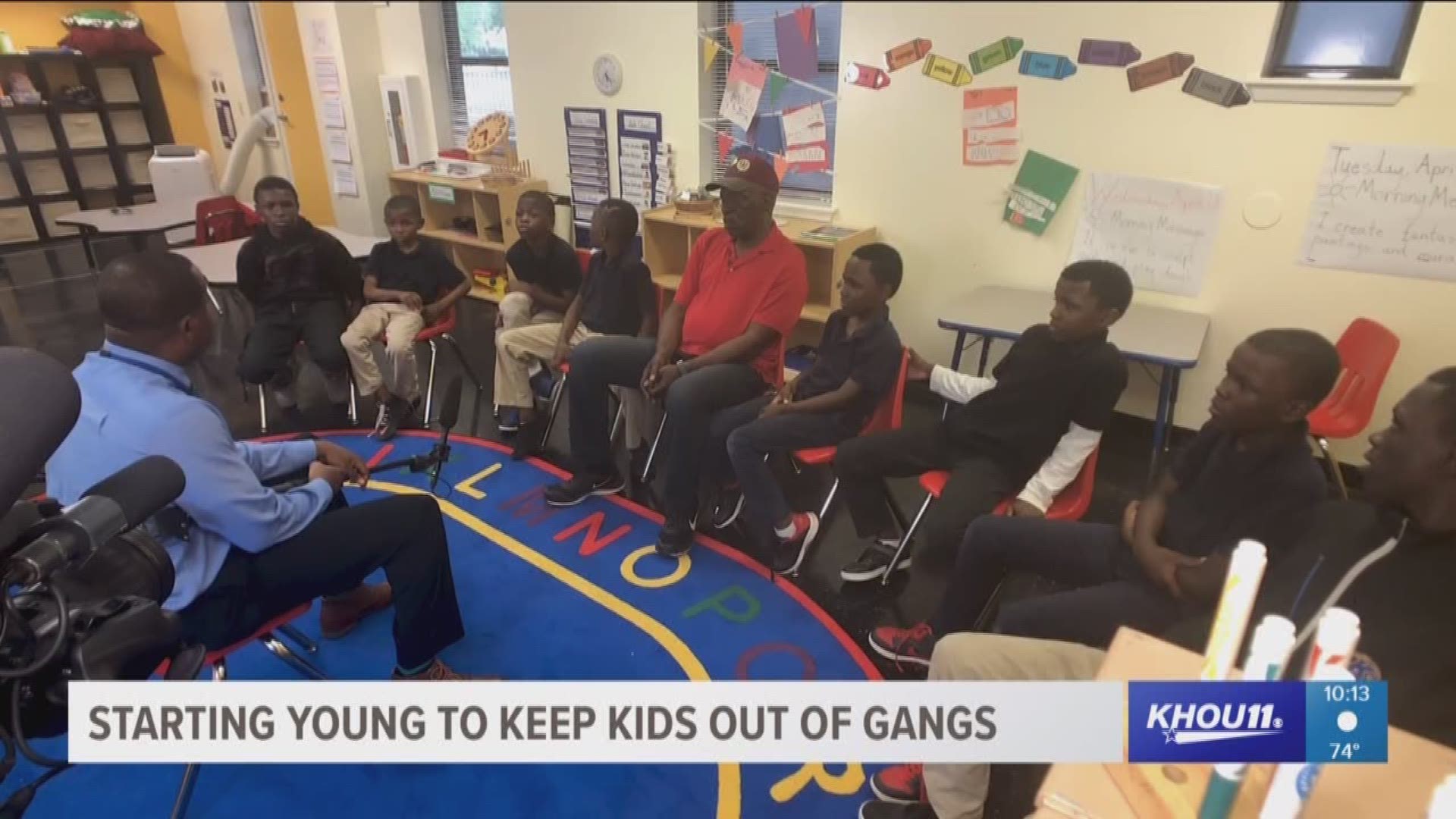

Mike Malkemes shares Gordon’s passion. Malkemes, a former Marine, founded Generation One, an organization that focuses on saving children from gang life at an early age. As much as Malkemes loves helping teens, his research found he must target pre-school-aged children to make a difference.

“We looked at everything we were doing and realized 0 to 5 (years old) is where everything has to happen,” Malkemes said. “The self-awareness, the self-regulation, the empathy, the trust, the unresolved trauma from bereavement and death was overwhelming everything else.”

Nine of every 10 students at Generation One lost their mom, dad, brother or sister killed in the last year.

Saving youth surrounded by violence, Noel Pinnock said, is a public health priority.

Pinnock leads My Brother’s Keeper, a program run by the city of Houston’s health department.

The aim is to cool youth violence, and gangs play a large pat.

“I think the number one issue or factor is that we have kids who are anonymous to all of us,” Pinnock said. “Anonymity is when you exist but don’t exist. Nobody wants to get up and live in a world or society that (doesn’t) know who they are.”

Pinnock grew up in Sunnyside in southeast Houston, one of the city’s most crime-ridden areas for gangs. Pinnock said the neighborhood drug dealer lived nearby and packed weight.

“I’m talking both grams and guns,” Pinnock said.

In March, My Brother’s Keeper and the Harris County District Attorney’s Office launched a first-of-its-kind juvenile intervention that focuses on providing mental health support and rehabilitation classes.

Harris County’s program is the first in the nation to apply to middle schoolers. Pinnock is optimistic about the results.

“We’re not competing with the gangs,” Pinnock said, “we’re not even trying to show them there’s a better way. We’re just showing them there’s another way.”

Gordon found his other way.

He no longer chooses to hide.

Most days he wears his black-buttoned uniform with patches on each sleeve promoting Operation Rescue. Now known as OG1, Gordon begs for teens’ attention, hoping to recruit them to a path far different from the one he chose decades ago.